I can count on one hand the times I’ve cooked the last year, living in Shanghai. Thanks to coupons on food delivery APP’s, not only is it often cheaper to have food delivered than to eat it at a restaurant, it’s difficult to make dishes yourself in your own kitchen and compete on price with the raw ingredients you have to buy (and cooking skills, but that is not the point here).

There was a time though, that this was even more extreme. A few years ago you could basically eat for free if you’d just change APP every day, each platform offering weekly coupons you could use. Now only Ele.ma and Meituan remain.

We saw a similar price war in 2018 and 2019 with sharing bicycles; Ofo versus Mobike. Ofo was the worst of them, the company mainly aiming to be the cheapest and growing through deposits from users. I never found an Ofo bike that was in decent shape. It always had at least one wheel bent, a handgrip missing, or worse, you’d scan the QR code and then discover that the bike had no chain.

In a rush, Ofo and Mobike also tried to expand overseas in Southeast Asia, Japan, the US, and Europe. Both brands burned through their cash. Ofo went up in smoke and Mobike had to retreat to just serve China, before being bought by Meituan.

But there is a winner here. HelloBike, a third competitor, focussed on lower-tier cities (getting 95% of its users from tier 2 & tier 3 cities), and now they’ve made their way to Shanghai, quickly replacing the Mobikes on the sidewalk. HelloBike doesn’t rely on a low price (although they’re still cheap). Rather, they’re embedded into Alipay, so you can quickly scan it and you don’t need to register a new APP. And they’re in good shape. And they’re everywhere.

Sadly for marketers, discounting is such a drug.

The IRI states that in the UK supermarkets, more than 50% of food & non-food products are now sold on discount, and that discount is now one of the most significant marketing expenses, usually costing more than TV advertising.

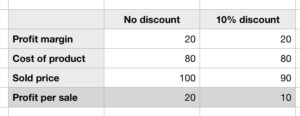

The main misconception about discounting is how much it eats into your profit. Let’s do a simple calculation. If your profit margin is 20% and you give a 10% discount, that means you cut your profits by 50%. In this scenario, you need to double your sales to break even, something a 10% discount is unlikely to do.

Besides this, there are more reasons to avoid discounts:

- You turn your product into a commodity.

- It signals low quality and low confidence, which erodes brand value. You’re saying to your customers “Yeah, we’re not really worth that much”.

- Discounting mainly benefits the people who already buy your product. If your product is non-perishable, they might bulk-buy or learn to buy on discount.

- There is no evidence that discounting increases loyalty. As soon as discounts stop, customers go back to their normal purchase patterns.

- In fact, the opposite may be true; customers who paid the full price before will be annoyed and reluctant to pay the full price again in the future.

- Rather than discounting, investing in a brand has much higher returns, especially in the long term.

Would you still buy Ferrero Rocher if it was much cheaper? Apple smartphones? Gilette razers? Nike sneakers? Nintendo is known for rarely lowering prices on their consoles for years after its release, and the same for any premium fashion brand.

These brands gain credibility from their pricing power. McKinsey states that 80 to 90% of incorrect pricing decisions are made by marketers who simply charge too little, not too much.

Discounting is an addictive habit that is hard to stop, because it contributes directly to short-term sales numbers, even if it comes at the expense of future profits, brand image and customer relationships. Customers, now with their closets full of your product, can sit out a few months to buy again, creating a vicious cycle: you need more discount to keep up sales levels.

It’s very hard for marketers to hold their ground when it comes to discounting, but here are some things that help:

- Use the Westendorp pricing model, helping you hit the range between too cheap and too expensive.

- Introduce different pricing models. Mercedes-Benz has the affordable A-class as well as the CLK. For GoEast Mandarin we offer private & group classes.

- If you must have an incentive, you can also operate from a strength, e.g. “Only 5 places left for this course”. If you must give away something, give away something else than your core product. This can actually improve the brand, rather than erode it (see figure 14 from ’The Long & Short of it’).

- If you must discount, offer it to groups that need it and can grow into full-paying customers, such as students (such as Apple is doing).

The reason why brands fail is rarely about lack of discounting. Mobike, Ofo, Toys R Us, Borders, Blockbuster, Thomas Cook, and Hummer didn’t fail because they weren’t cheap enough, but rather that they didn’t offer anymore what the customers wanted, and somebody else offered it better. Discounting wouldn’t have saved them, and to have relied on it instead of saving their business is just lazy.

Brands may succeed on low pricing, but it’s very rare. When brands fail, when customers don’t want to buy your product, it’s rarely because of pricing alone. The advice on discounting is: Set your normal pricing right, and just don’t discount.