Marketing theory comes down to how you think marketing works.

Imagine 全家FamilyMart would open up a 5-star restaurant in downtown Shanghai. Candles on the table, waiters suited up, silver cutlery. And FamilyMart would serve their microwave meals, touting their high-quality taste. It’d be fun, they’d invite 网红wanghong to magazines, and they’d get some serious PR.

If you think marketing’s role is to create awareness simply by broadcasting messages, this does a great role.

And part of this is true. 科罗娜Corona beer isn’t hurt by covid-19, because sharing its name with a worldwide virus doesn’t hurt its core brand image (light Mexican beer drank on a white beach). And fashion brands like Primark, Uniqlo, H&M, and Zara are often criticized for their poor ethics on underpaying factory workers in poor working conditions, but remain popular because it doesn’t directly hurt their core brand images about low-price fast-fashion (if anything; it reinforces it).

But if you think marketing works by creating or reinforcing mental connections, then the above PR stunt by FamilyMart is clearly wrong. FamilyMart does not have a reputation for great food taste, and it’s unlikely it can pull that off with a single PR stunt. Their brand reputation is based on the ease of availability (there’s always a FamilyMart near you), the speed of their service (you can enter and exit with a warm microwave meal in mere minutes), and a low price (12 RMB for a lunch). Doing a 5-star restaurant PR stunt contradicts FamilyMart at the core of its reputation: exclusive, slow, expensive.

This is why 汉堡王Burger King’s moldy whopper ad was so divisive among marketeers. Some thought it was a great PR success, others thought an image of rotten food is contradicting Burger King’s reputation built on taste and enjoyment. Another brand, 赛百味Subway, is facing a PR crisis because of a lawsuit that says their tuna isn’t tuna, but ‘a mixture of various concoctions’. This hurts at the heart of Subway’s brand, built on fresh ingredients. 吉莱特Gilette launched their #MeToo commercial to encourage men to be better against women, but its tone was highly accusing against its core audience, who for a large part hated it. Holden cars announced it was no longer made its cars in Australia: which was the whole point of the brand — Australians buying Australian-made cars — and not much longer the brand was scrapped by GM. These examples all create awareness through broadcasting messages, but brands are hurt in the process.

There is a middle ground though. When 保时捷Porsche launched the 卡宴Cayenne SUV in 2002, marketeers said it’d be the end of Porsche because it contradicted its reputation for sporty and fast cars, and yet over 1 million of these models have been sold, and Porsche’s best-selling vehicle now is the smaller Cayenne; the Macan SUV. The hugely popular Cadbury Gorilla advert showed a man in a gorilla suit drumming to Phil Collins, which had nothing to do with chocolate or Cadbury except for the swatch of purple in the background, and a loose proposition around ‘joy’. When Peloton, a brand of spinning bikes, showed a husband gifting his already-skinny wife an exercise bike, it looked like an abusive relationship, but the benefits of the product were displayed nonetheless and the brand did gain traction.

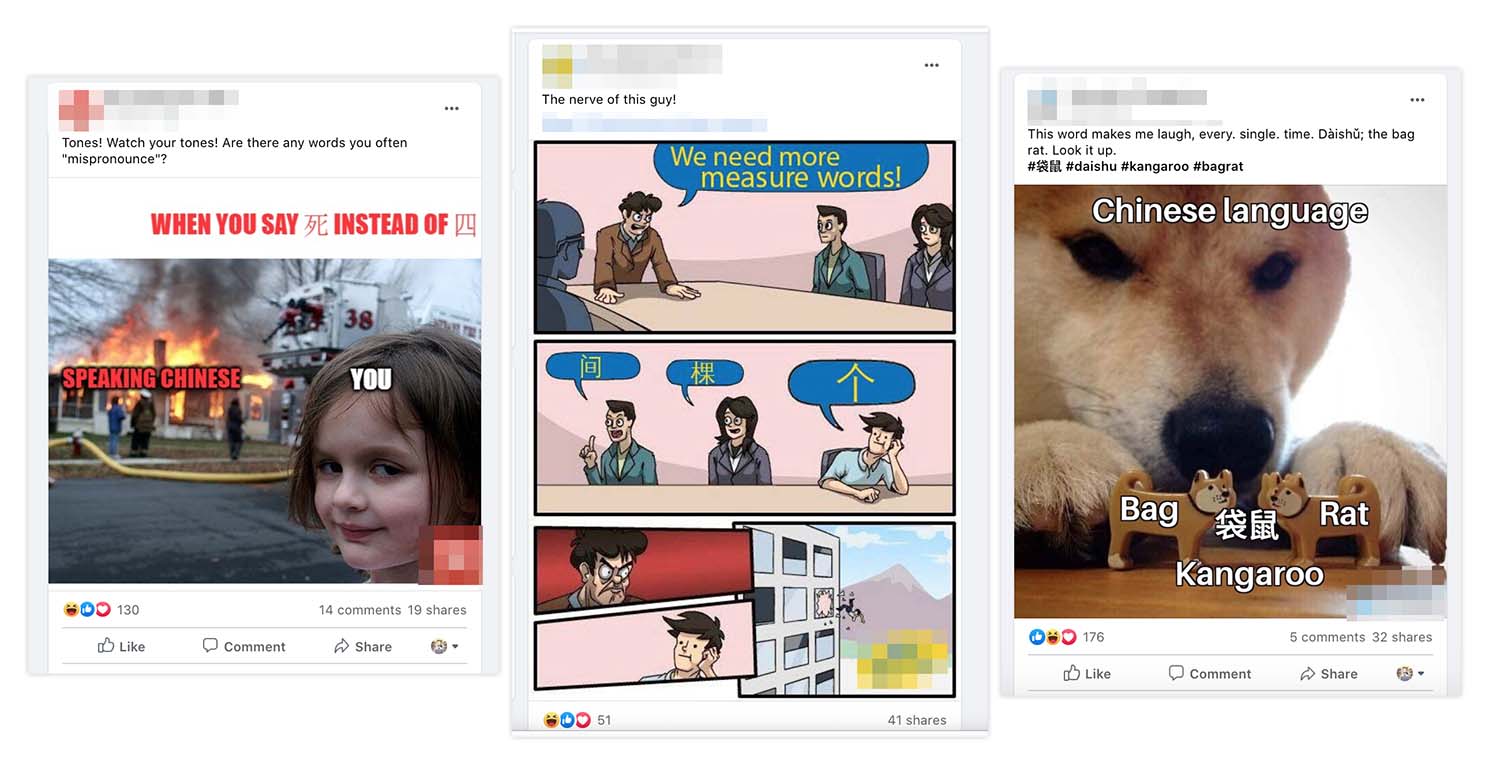

So some of GoEast Mandarin‘s competing Chinese language education companies love to post memes on social media. If you think salience and awareness is marketing’s prime goal, and if you think these memes create salience — then this works because people click and like these posts. But if you think marketing works by creating mental associations, then this makes you look like a teenager, rather than a professional language education institution.

There’s no answer. It depends on how you think marketing works.