The paper faces of Mao and Qin Shi blacken and deform as fire takes the bills. I never knew burning money to be so beautiful, even though this money is fake, burned to honour ancestors. Eva’s dad twists the poke and turns over more unburned ghost money (冥纸 Míng zhǐ) into the flames. Half an hour later, the ashes still glow in the night, incensed by each gust of wind.

We’re on the doorstep of the rural house in Nantong, and in the living room stands a table all set for dinner; two candles tower over eight bowls of rice, and four plates of vegetables, fish and meat — all as if the guest will arrive any time soon. But this food will not be eaten, at least not by living people. Like the money, it’s for the ancestors and will be thrown away later (祭祖 Jì zǔ).

I wonder if when I’m no longer here, someone will also set a table like that, burn money for me. Remember me. Be grateful for my life.

The ritual is eerie, but beautiful as well. It’s not the ashes or the uneaten fish that matters, it’s three generations making sure they have not forgotten about those who came before them. In the cold night of Nantong, every person took turns kneeling in front of the bucket of burning money to pray for the dead. They giggled when I did, maybe the scene so out of place, a bearded foreigner participating in this ritual. I kneeled, eyes closed, while memories of my own grandparents flashed in my mind.

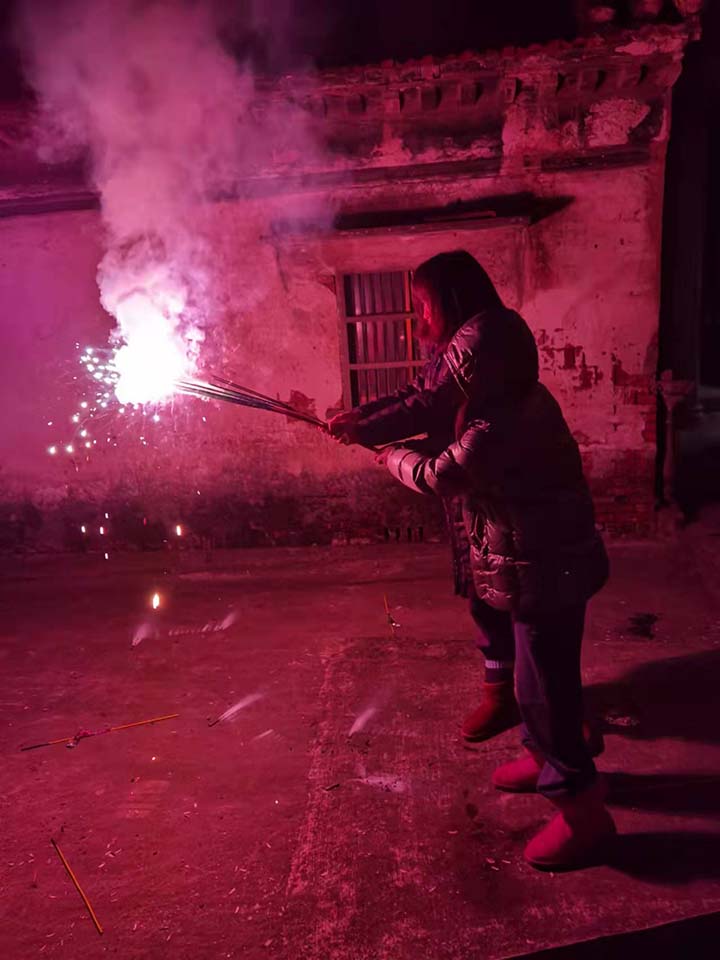

Chinese New Year is riddled with rituals and customs, all about fortune and misfortune. I’m afraid of doing something wrong. Later, we use one of the big candles to light fireworks, and when all the firework has scared the evil spirits, I wonder if I can blow out the candle. “You sure?”, I ask, for I do not want to do something wrong and condemn misfortune on anyone.

Earlier that day, we hung up new years banners, with blessings in form of an idiom or simply the character ‘福Fú’ that means good fortune. 福 can also be hung upside down, so the fortune can flow out. All the gates and doors need to get some banners. The doors inside the house need a green one on the left, and a red one on the right. The door to the kitchen received a blessing specific blessing to cooking, something about a hundred flavours. We removed the banners from last year, because you cannot use them again — even if their colours aren’t faded in the sun yet: their blessings have been used up. In some places, I could see the glue and sticky tape remains from several years.

The Spring Festival is its own period of time, people no longer think about ‘Monday’ or ‘January 31st’, but dates are changed into ‘除夕Chúxì’ (Last day of the old year), and ‘初一 Chū yī’ (first day of the new year), ‘初二 chū èr’, etcetera.

Fireworks, for instance, is for the evening of Chúxì, as well as the morning of ‘Chū yī’ and ‘Chū wǔ’ (the fifth day of the new year). You should not sweep the flours or wash clothes on Chū yī, because it brings bad luck (as if you sweep out the luck from the house). We should have given the red envelopes (红包Hóngbāo) to kids on Chū yī, but because Eva’s sister was staying in a more comfortable hotel in the city, we gave them on Chúxì. So some pragmatism is allowed.

On Chúxì, we also had dinner (年夜饭Nián yèfàn), very much like a typical Christmas, but the plates had to amount to nine, because in Chinese 九Jiǔ sounds like ‘long lasting’. A secret tenth plate was added after everyone took the photo. We sat with eight people, two on each on a tiny wooden bench on a square table. On Chúxì we had rice balls (汤圆Tāngyuán) for breakfast, and three types of vegetables (each name similar to good fortune in one way or another).

I heard about Chinese New Year celebrations before and read some articles about it online. But only now I realize how beautiful as well as ‘复杂Fùzá’ (complex) it really is. I guess any culture is always weird to any outsider, but you will never notice how peculiar your own culture is, for what is home is your normal. Why do Westerners put a tree in the house for Christmas? Religion isn’t the same as culture, because in the first place, religion is a way to wonder about the mystery of life of which we ourselves are part of. It all makes for weird, complex, yet beautiful rituals.

Join me for a walk in Mandarin around the area, recorded for GoEast Mandarin.