This is one of the many paragraphs from ‘H is for Hawk‘ by Helen Macdonald that stood out for me and still lingers in my mind weeks after reading it:

“I think of what wild animals are in our imagination. And how they are disappearing — not just from the wild, but from people’s everyday lives, replaced by images in print and on screen. The rarer they get, the fewer meanings animals can have. Eventually rarity is all they are made off. The condor is an icon of extinction. There’s little else to it now but being the last of its kind. And in this lies the diminution of the world. How can you love something, how can you fight to protect it, if all it means is loss? This is the distanced view of modern nature-appreciation.”

I’m reminded of a woman in a Dutch supermarket who lifted a pack of chicken legs from the fridge, only to react disgusted when she saw a small feather on one of them. If prompted to answer, she’d probably know, but I do wonder if at that moment she realised she was holding a dead animal and not a ‘fabricated’ supermarket product, constructed for perfection.

At least surveys show that kids in the UK no longer know where butter or cheese or eggs come from. Then there’s this tweet by a mom who’s son thought bats where fictional creatures made up for Halloween. In the Netherlands, pine cones are now sold in garden centres (for five Euros!) — and the only outdoor cows I’ve seen in China where ‘art statues’ — and the only collections of trees to walk through within an hour’s drive of my home in Shanghai are carefully arranged parks that are raked and cleaned twice a day.

The rarer nature becomes, the increasingly difficult it is to enjoy it for its own sake. We go into a forest like a holiday and turn on our mindset: “Okay, NOW I’m really going to enjoy this”, even though one cannot and should not force it like this (It cannot be pursued, it can only ensue (‘Man’s Search for Meaning‘)).

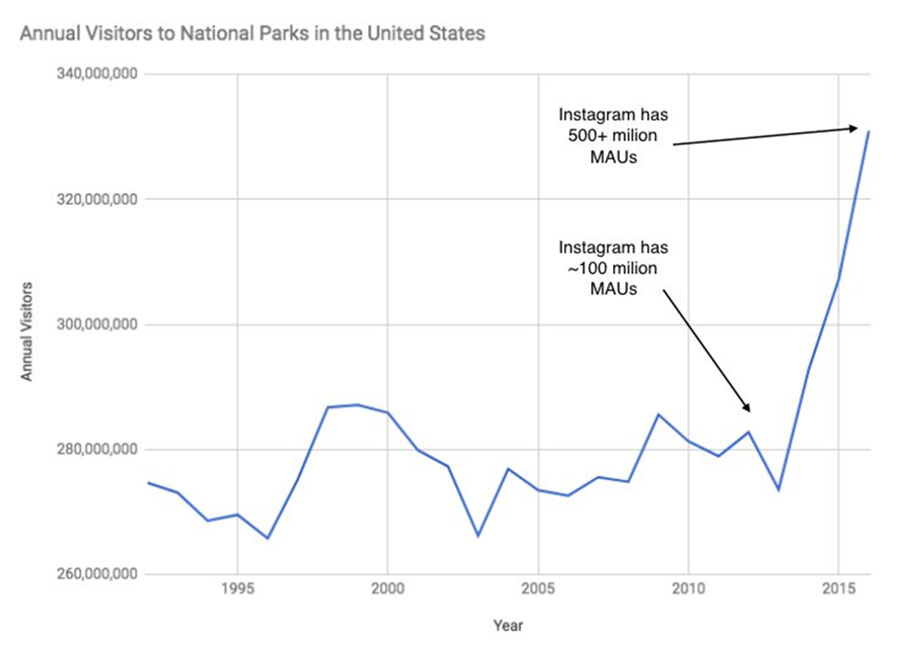

In ’21 Lessons for the 21st Century’, Yuval Noah Harari makes the point that we’re increasingly distancing even from ourselves, as we increasingly judge our emotions by the amount of likes we get, and we barely notice what we ourselves feel. We are certainly doing this to restaurants, point being made by Kevin Alexander: “…the people crowding the restaurant were one time customers. They were there to check off a thing on a list, and put it on Instagram. They weren’t invested in the restaurant’s success, but instead in having a public facing opinion of a well known place.” Visits to US national parks have skyrocketed in recent years, something that perhaps only coincidently coincides with the advent of Instagram.

Nature isn’t about to get any less rare, but we can enjoy it for what it is. (I think this also applies for cultural things, such as old buildings, which are increasingly rare in Chinese megacities.) As for nature, I’d say the antidote is twofold. Enjoy only the place you’re currently in, not any online social feed. Enjoy nature for what it is — and not what it can do for us. And accept its flaws, for it has many. Sometimes it’s far to drive (it’s always farther than the shopping mall) — and sometimes you just want a chicken leg and not a feather on it. But it’s important we accept these flaws, like as the occasional rain-shower that soaks you to the bone, because the alternative is much much colder.