Written: August 2022 — Updated: August 2024

Open any history book or article about Shanghai and you’ll probably read something condescending along the lines of “Shanghai was a backwater fishing village until the foreigners came in the 19th century.” And it evokes a visual image of fishermen on the banks of an empty yet huge river delta, ready to be modeled by the hands of foreign invaders with piles and piers, wharves, and art-deco bank buildings. An easy to believe image as well. But while foreigners did help turn Shanghai into one of the biggest cities in the world, their arrival shouldn’t erase the overlooked history of Shanghai before their arrival, which was way more than just a fishing village. And some traces still remain visible today, if you start looking for them.

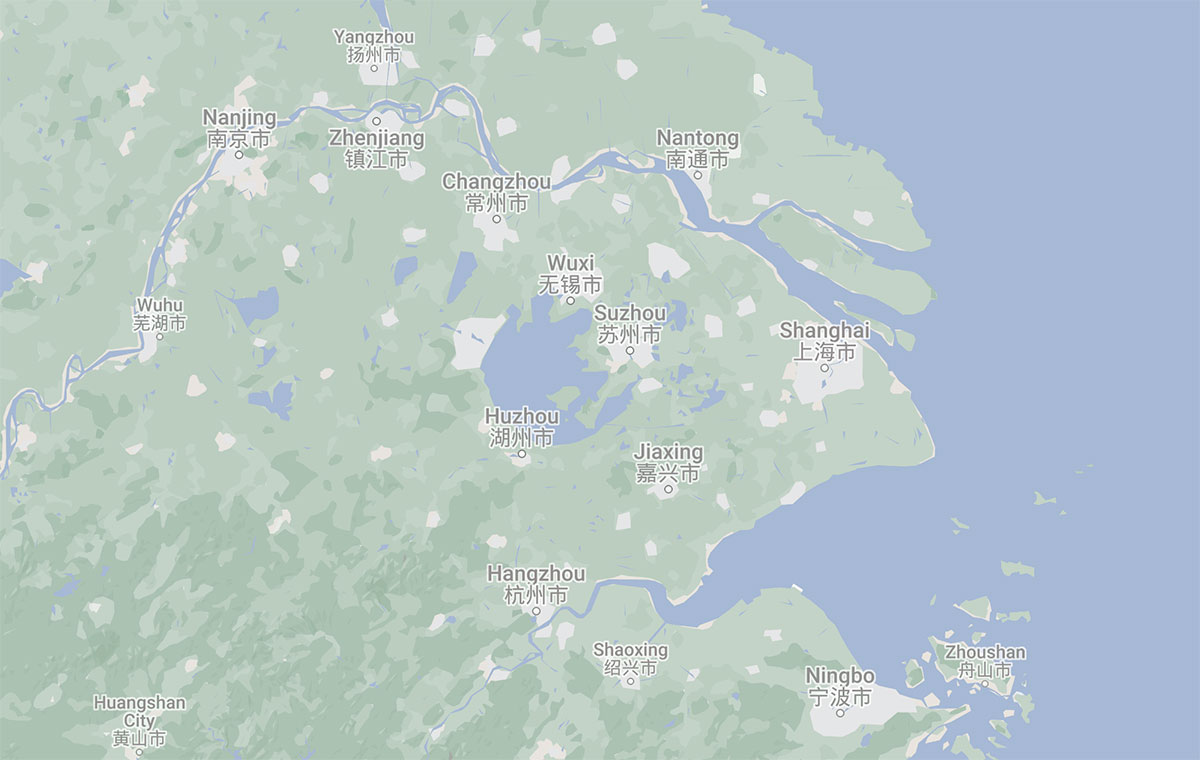

The area of Jiangnan (江南)

People lived in the area of Shanghai 6,000 years ago — testimony of pots and tools found in the ground — but a city started to take shape during the Spring and Autumn period (春秋时代) (771 to 476 BC), on the banks of the river that runs directly through Shanghai today, Suzhou Creek (苏州河). “Was this settlement Shanghai or not?” isn’t an interesting question to me, because what follows is a long list of dynasties and rulers, and new settlements with changing names in the area that later amalgamate into Shanghai. All these histories and cultures (including Western influences) are now part of Shanghai as well.

What’s more useful is to look at the province as a whole. Today, Shanghai is its own province, similar to cities like Beijing and Chongqing, but the area of Jiangnan (which was later split into Jiangsu (江苏) and Anhui (安徽) has been one of the richest areas in China since the Eastern Han dynasty (25–220 AD). Crops were grown, but dozens of cities also undertook profitable trade in many products with regions in Asia, and even as far as Jeddah.

If you go to a city or district museum in any of the cities in the area, you’ll find porcelain and jewelry from the wealth of the past centuries, as well as recreations of boats and wharves. And it serves a message as well, as usually, the exhibition ends with “let’s remind us of our precious past to create a new and better future.”

Shanghai wasn’t the most important city of Jiangnan, and only in 1291 it became a county (县), when five small villages were put together into Shanghai County (上海县).

Several cities that are part of Shanghai today, were at that time separated by a dozen kilometers or more — and these were often bigger and richer than Shanghai was. In the Yuan and Song Dynasties (960 to 1368), Qingpu (青浦), Jiading (嘉定), and Songjiang (松江) became wealthy trade cities, dealing in goods like grain, cotton, silk, and textiles.

Shanghai before the foreigners

Shanghai grew though. When Qingpu’s rivers silted up, part of the trade relocated to Shanghai. In the 15th century, Shanghai was already known as a culturally rich city — perhaps not in the whole of China, but there was business beyond fish. Shanghai had sandalwood, turtle shells, bird nests, and exported goods like cloth, silk, pottery, tobacco, and dried fruit. Shanghai had poets, musicians, scholars, and politicians. There were temples for several religions and philosophies; Taoism, Confucianism, Buddhism, Islam, Christianity, and local religions. There was sewage, over a hundred bridges, trade unions, schools, a district office, tea houses, whore houses, and loads of restaurants and shops and merchants from all over China.

Already the population was 200,000 or 300,000, and the city was rich enough to be frequently attacked by Japanese pirates (倭寇) and Chinese bandits (who joined the Japanese in their raids), so in the mid-16th century, a city wall with six gates was built. This one still exists, although only a tiny portion. You can still see the full outline on the map today though.

Especially from the late 17th century, when the Qing dynasty started, Shanghai started to grow further and rival Suzhou as a city of importance. 外马路Wai Ma Lu (Outside street), which still exists today as a road, had 20 wharves, over 130 registered guilds, and over 3500 registered boats. When the foreigners arrived they called it a ‘forest of masts’. With all this, it’s clear to me that Shanghai was way more than just a fishing village.

Traces today?

Thousands of traces of Shanghai before the foreigners still exist today, if not millions. Most likely they’re shapes on the map or street names (most famously Laoximen, or “Old West Gate”), or the name Xujiahui (徐家汇) which has roots in the late 16th century. There are also museums full of recreations and pot shards, coins, jewelry, and documents. But real buildings from before the foreigners arrived? Very few? It seems mostly bridges, pagodas and temples survived. There are also plenty of water towns but it’s hard to say which are real or recreations. Just compare the two images of Zhujiajiao (朱家角). It’s likely that only the bridge is still standing.

Another example is the Jing’an temple (静安寺). Signs will say it was built in 1216, but it was demolished during the Cultural Revolution (1966 to 1976) to make space for a factory. The current building was only built in 1983, albeit in the same place.

Prime examples perhaps of buildings that are still standing are the Wanshou Tower (万寿塔) from the 8th century, in Qingpu. And Songjiang has one of the oldest mosques in China (from the Yuan dynasty). In Chuansha (川沙县), located in Pudong, you can still see parts of a Ming dynasty (1368 to 1644) city wall, made also in defense of Japanese pirates. So too in Lao Baoshan (老宝山), Nanhui, Fengxian, Zhelin (柘林), Jinshan, and Chongming Island. In the Fengxian district stands still a 3.9 kilometer old stone sea dike. Longhua pagoda (龙华塔) stands more in the city center and is over one thousand years old. Also, the Ningbo Guildhall (四明公所), built in 1803 still stands — or at least the facade.

Searching for old Jiading

To give a sense of how hard it is: I went looking for traces of the old wall in Jiading. The museum showed a model of Jiading in 1940 — not even that long ago — with a full city wall. Yet today, streets and bus stops carry the names of old, as well as a bridge named ‘西城河桥’ (West Wall River Bridge) and ‘城河’ (Wall River). The canal is still here, but only a few segments of the wall remain (partly rebuilt).

The tower on the miniature city above, still exists. Fahua Pagoda (法华塔) was built in 1205-1207 during the Southern Song Dynasty), restored several times, and even used by the Japanese as a post during the Battle of Songhu (淞沪抗战).

Shanghai’s city wall

The biggest and most obvious ‘structure’ of Shanghai before the foreigner’s arrival is its old city wall. But sadly, the wall was dismantled very quickly in the early 20th century. The walls in Nanchengqiang Park (南城公园) are partially recreated, but an old segment at Luxiangyuan Road (露香园路) still survives, as well as a bigger segment on Dajing Road (大境路). But why is this so part of history cherished so little? We cannot enter this building, there’s only a public toilet to the side.

The best example of Shanghai before the foreigners is an old sluice (普陀区元代水闸), built around 700 years ago, designed to stop the tide and the silt generated by the water flow. It now sits underground in a museum, but still obvious is the scale and the advanced technology. It has hundreds of wooden piles to protect against the currents (some carved with characters), and limestone slabs joined by iron tenons.

Why is there so little?

What remains mostly of Shanghai before the foreigners arrived are pots and tools in museums. But why have so few buildings survived and been preserved? A few things can be blamed. One reason is simply that most houses back then couldn’t survive for almost two centuries of time. Early foreign arrivals lived in the walled city of Shanghai and complained that the roof would leak and mosquitos would enter the house from all sides.

Another reason is that when the foreigners decided to settle, they had little respect for Chinese property — forcefully taking land and using Chinese wood carvings as firewood. Loads of Chinese buildings were destroyed in a rapid pace, and already in 1847, there were 56 foreign buildings around the former walled city.

The Small Swords Society (小刀会) and the Taiping Rebellion (太平天国运动) barely damaged Shanghai, but the war with Japan did, massively, with bombs being dropped and shells fired. And mostly buildings outside of the foreign concessions were destroyed.

There’s the principle that old buildings are preserved best when a place was rich and became poorer, such as Venice or Bruges. With Shanghai, it was quite the opposite, as it (partially) changed ownership multiple times. The foreigners arrived during the Qing Dynasty, forcibly took over parts of Shanghai, then it was the Kuomintang ruled over the Chinese parts, before the Japanese ruled over everything — and ultimately the Chinese Communist Party (including the chaotic Red Guards, for a while). And each of them had different plans for the city, with few buildings holy enough to be protected. Also, old buildings often need funds to be renovated, funds that at many stages of the past two centuries were lacking. Still, the traces are there, if you look.