Many Shanghai-based expats (like me) have seen their Twitter accounts grow — explode — in terms of impressions & followers. There’s a lot more to talk about Shanghai than during normal days. The strict lockdown has given us and everyone we know new challenges, which are not just different for each district, but also change by the day.

But we aren’t just tweeting more, there’s also way more attention for what we tweet. And I think all of us have discovered how much some tweets are shared, like as if either the tweet is of some highly flammable substance — or we’re adding oil to the fire.

It’s really interesting because I think all expats still living in China these days, dearly love the country. Most haven’t seen their family in their home country for two or three years, or they’ve gone through two or three weeks of quarantine in a hotel to do so. So we love China, but not this lockdown obviously. Are our feelings true? What if negative tweets get you more followers?

I don’t know how to feel about this dynamic. Of course, it’s nice if you get more followers & interaction and it’d be a lie to deny otherwise. But does it influences what you say? At the cost of your authenticity?

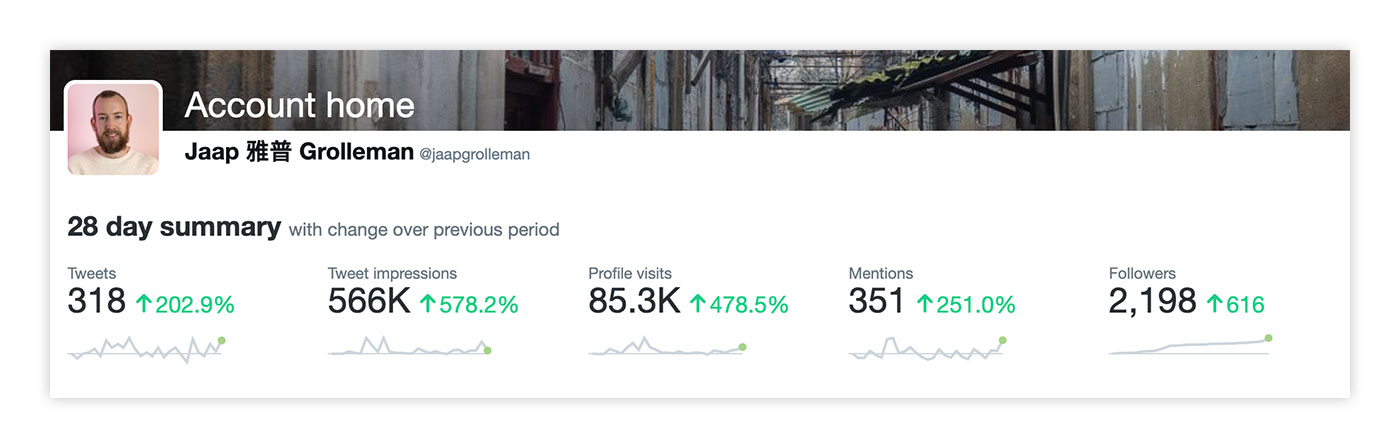

I can only speak for myself so I’m sharing my thoughts & numbers here (screenshots from May 11). Honestly not trying to show off: on normal days my account & blog barely has followers or retweets, and I’m sure some other expats have numbers with a few zeros added to the numbers.

So for comparison, in February (also a 28th day period), my account got 7.3K impressions — a huge difference with the last 28 days.

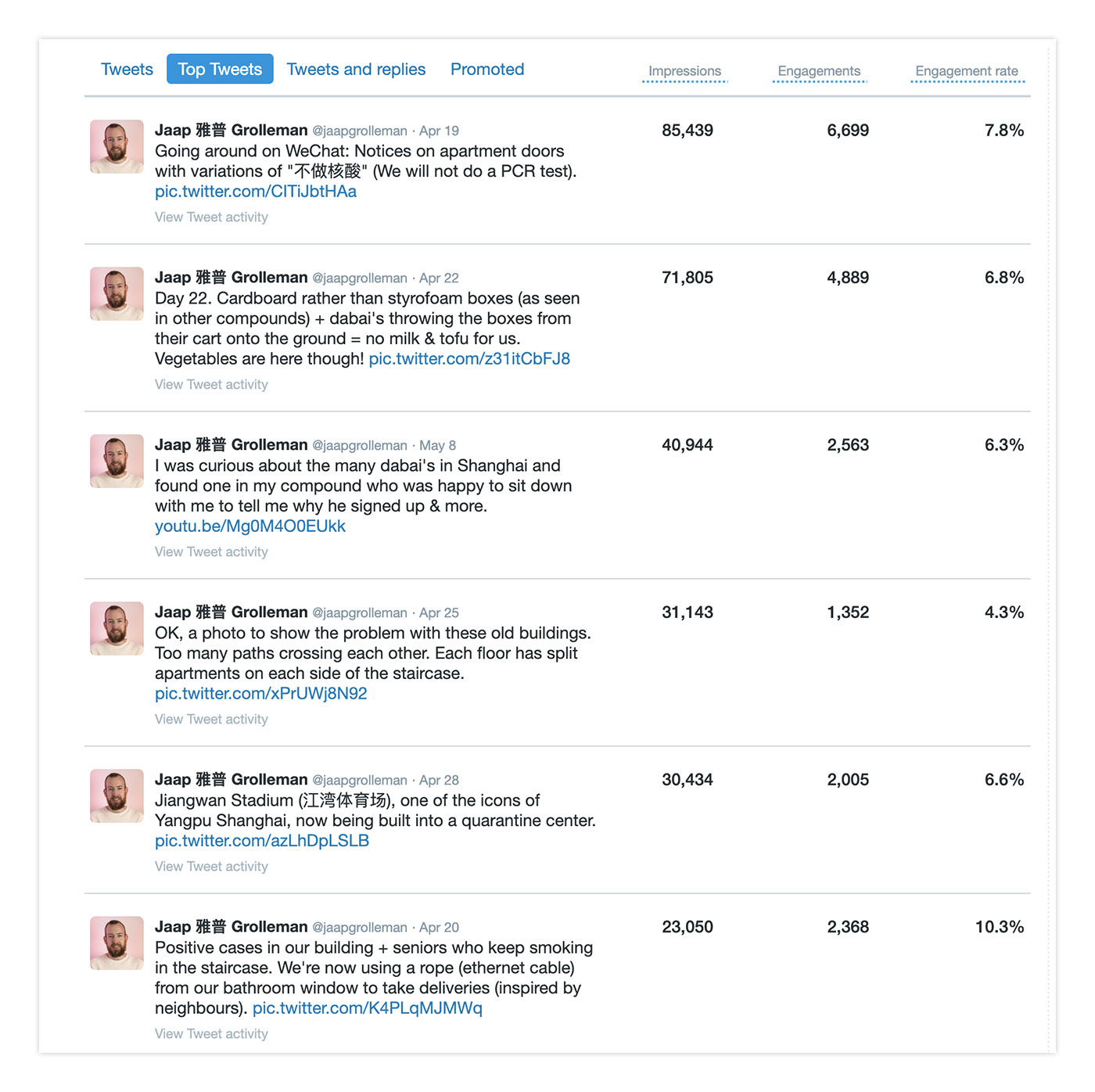

Looking at my top six tweets, I think three quality as a negative sentiment, two are neutral, and one a positive sentiment. Actually, when I look at my top twenty (here if you want), I think ten are negative, six are neutral and four are positive.

Negative tweets

The situation in Shanghai was and is pretty bad. People couldn’t get food or medicine, in some exceptional cases, dogs were clubbed to death, kids were separated from their parents, and fences or barbed wire locked people in their buildings.

For me, tweeting & writing has always been about what I see and how it makes me feel. So lock me in my house for several weeks and of course, some of my feelings are going to be a bit negative. Also, nearly all of my interaction with neighbors or colleagues, and friends has been reduced to WeChat. And so I’ve tweeted for instance about people close to me losing weight, and also our milk having exploded.

That said, there’s also some stuff I didn’t upload such as a fight in my compound with an old woman who I honestly think is mentally ill, or at least lonely enough to resort to such anger.

Positive tweets

There’s a lot of research about that on Twitter, bad news spreads faster than good news, but luckily I’ve also found that positive news can get attention, for me most notably my interview with a volunteer, or how the mood is changing — tweeted more in the end of the recorded 28 days rather than the start.

Content from others

I normally never tweet content from others. What’s the point? But now I did post a famous stadium in the neighborhood being converted into a quarantine center, and a compound in the neighborhood being opened. It feels a bit lame but I also think this content wouldn’t make its way out there otherwise.

Outrage has its purpose, but also an agenda

My feeling is the parent & child separation stopped when people were outraged, outraged enough for the French Consulate in Shanghai to write a letter. If that hadn’t happened, maybe parents & kids would still be separated. For this, outrage is good — a sentiment echoed by Naomi Wu:

But I also found how negative tweets attract a whole new audience, mostly far-right who whatever the circumstances think “China bad”. Tucker Carlson took two sentences from my blog to push his agenda against Biden. But you could say the same about Chinese state media though, with overly positive news.

Inflammable?

I don’t think many expats are very worried about repercussions, unless you start name-calling and insulting people higher up. But I doubt that’s anyone’s real intention. As said, nearly all the expats still left in China deeply love the country and it’s people — just not the way this lockdown is handled.

The interesting part is that expats in Shanghai who suddenly got a lot of new followers, maybe feel they can quickly amass some new followers with some bad news. Maybe tweak the wording a bit, maybe share a bit more? Some people have been called out, fairly or not — even I wouldn’t dare to judge others whether this is intentional or not (which is why I censored the name, because I feel it’s a bit harsh).

I don’t think there’s any answer to this. The situation was and is bad. It may be pleasing to some to live in outrage and see how bad China is doing, others want to showcase how good China is doing. Others like me will feel they are objectively documenting what’s happening — which also is not totally true even if we think our intentions are genuine.

Maybe Twitter is bad for nuance and people should just go back to writing long blogs (a move unlikely though one I’d welcome).

I think though, that if there is happiness from a tweet that has gone ‘viral’, it’s a fleeting, shallow kind of happiness. Not as profound as the happiness of having created something meaningful, such as the interview with Geng. Even if less people see it.