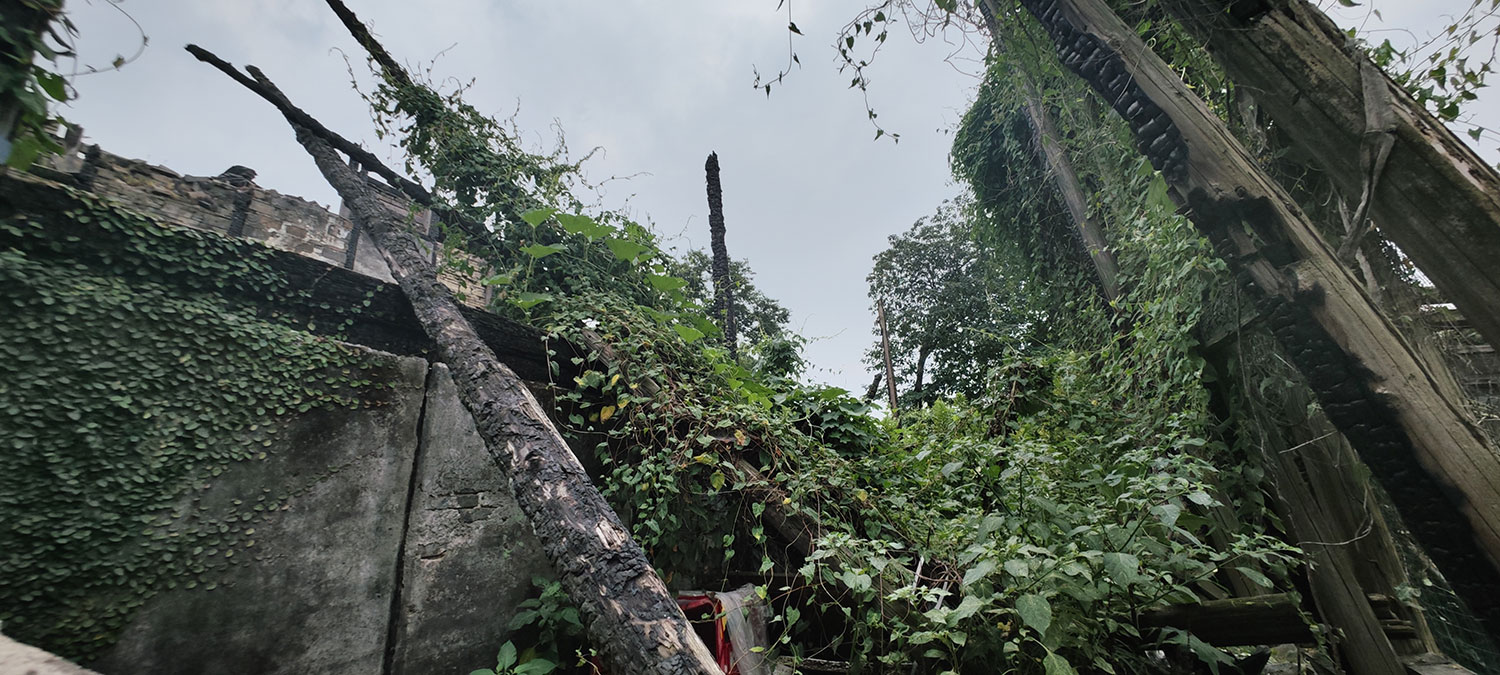

“Our neighbors left, the house next to theirs burned down and it also ruined their roof.”

Had he not told me this, I might have not noticed the charred beams.

We’re in Pinghu (平湖市钟埭老街) and the man lives in a house alongside the Corridor Shed (廊棚), which was built about a century ago when China was a young republic. It’s a packed house inside, and the story is the same as in all forlorn towns: “Most people have left already.” And it’s true. In many of the houses, you can literally look inside (and out again) from many angles.

A street away from the canal, a church service is going on and the average age runs pretty high. A woman asks: “Are you Christian as well?” I just nod to keep it easier (and to stay quiet).

There are some plaques to memorize the resistance against the Japanese last century, an old library, and an old city house. But for the rest, the street looks waiting, lost. It won’t be renovated, ever.

The end of the old street is more green. We find the Guo Si Bridge (国寺桥), a 250-year-old bridge (or rather, a stone beam) that crosses a tiny canal.

The plaque mentions the bridge, tiny as it is, was listed as a heritage twenty years ago, and also lists its numbers, and that’s how you really know it matters.

Chinese brands and places love numbers, even the Party does. How long since it has been founded, how many stores a brand has, how many people buy there, or how many products it has. It’s how you can know things are important. Numbers.

And so the plaque states that Guo Si Bridge is 9.8 meters long, 1.94 meters wide, 2.8 meters high, and the archway of the bridge is 3.03 meters wide. Accurate to the second decimal.

And in all the uncertainty of this area, at least nobody can argue with those numbers.