‘Nine dikes port’ (九圩港) lays on the outskirts of Nantong, cornered by highways and the ever-expanding industrial harbor of the city. The area is a collection of vegetable gardens and rural houses, tied together by one-car-width roads, and it feels a bit like a campsite. Everyone who enters changes. They soften up, forget about work, their Putonghua changes into the Nantong dialect, and even their names change: Eva is named ‘Little Second’ (小二侯) here.

A dozen dishes are spread out on the table. A 2021 calendar hangs in the dining room, stuck on January. The clock shows the wrong time, yet everyone arrives at roughly the same time. Everyone is somebody’s someone: a friend, my mother’s elder brother, my mother’s elder brother’s wife, and childhood companions are referred to as siblings: my younger sister, my elder brother. Nearly everyone has grown up here, and half of them still lives here permanently, the other half coming back only during holidays.

One of the cooks is a former red guard referred to as Dajiu (大舅); uncle, and his cooking skills are widely praised — the fact his wife helps cooking is ignored. Most food comes from the lands here; beans, pak choy, potatoes, poultry, and three big breams, one of which I caught and handed over to the chef. In the Netherlands we don’t eat bream, but here they do. Every bite is full of fishbones, unless you pick the meat from the belly. But it tastes good.

And dinner here is unlike dinner in Shanghai. Everyone is relaxed, stories and various bottles of alcohol pass over the table, and there are no phones in sight. Here’s the type of talk that friends have when they haven’t seen each other for a long time. “Where to put the cola?” a child asks, to which an uncle yells back: “Only bowls here, no cups.” (“只有碗没有杯子.”)

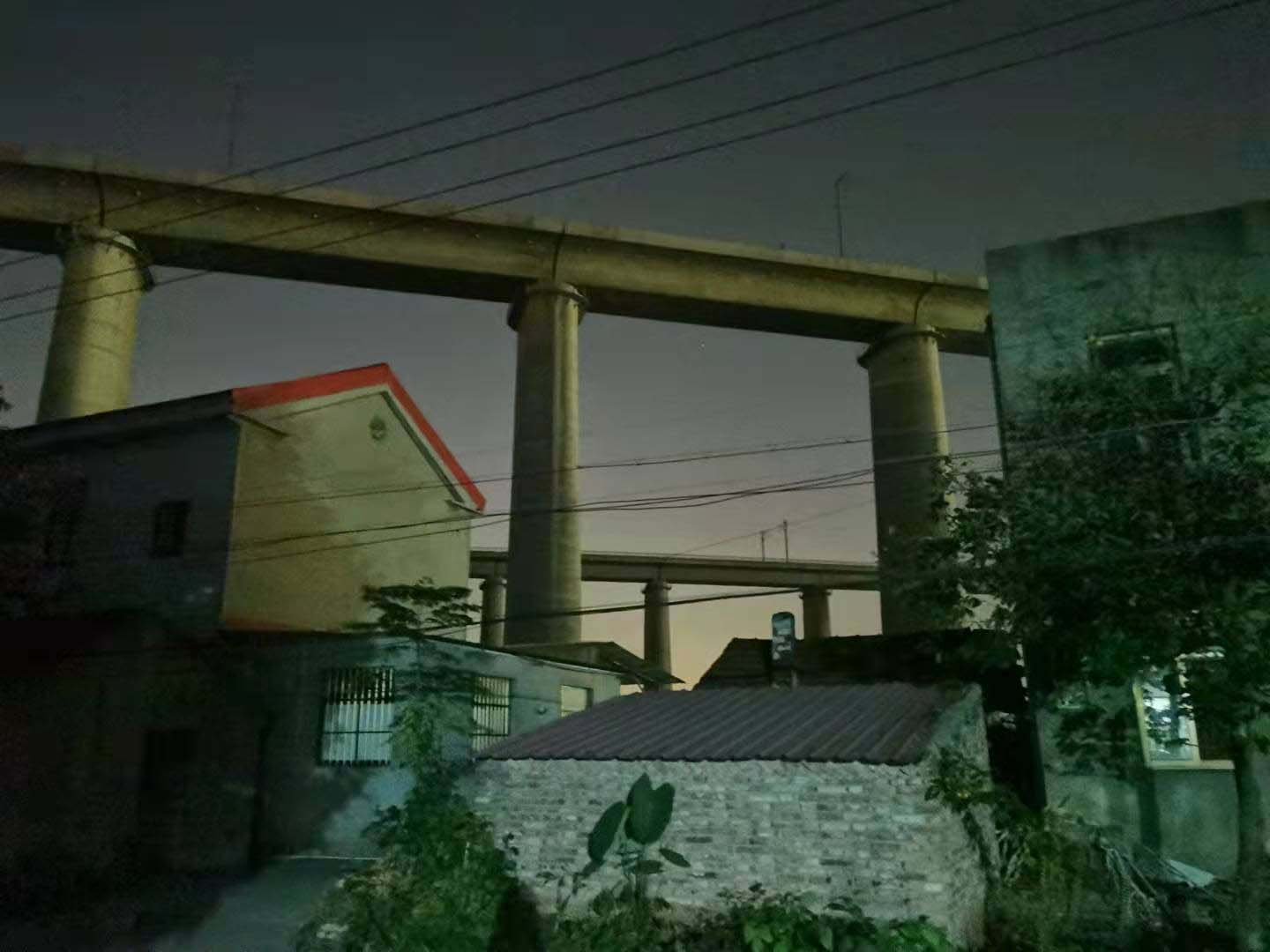

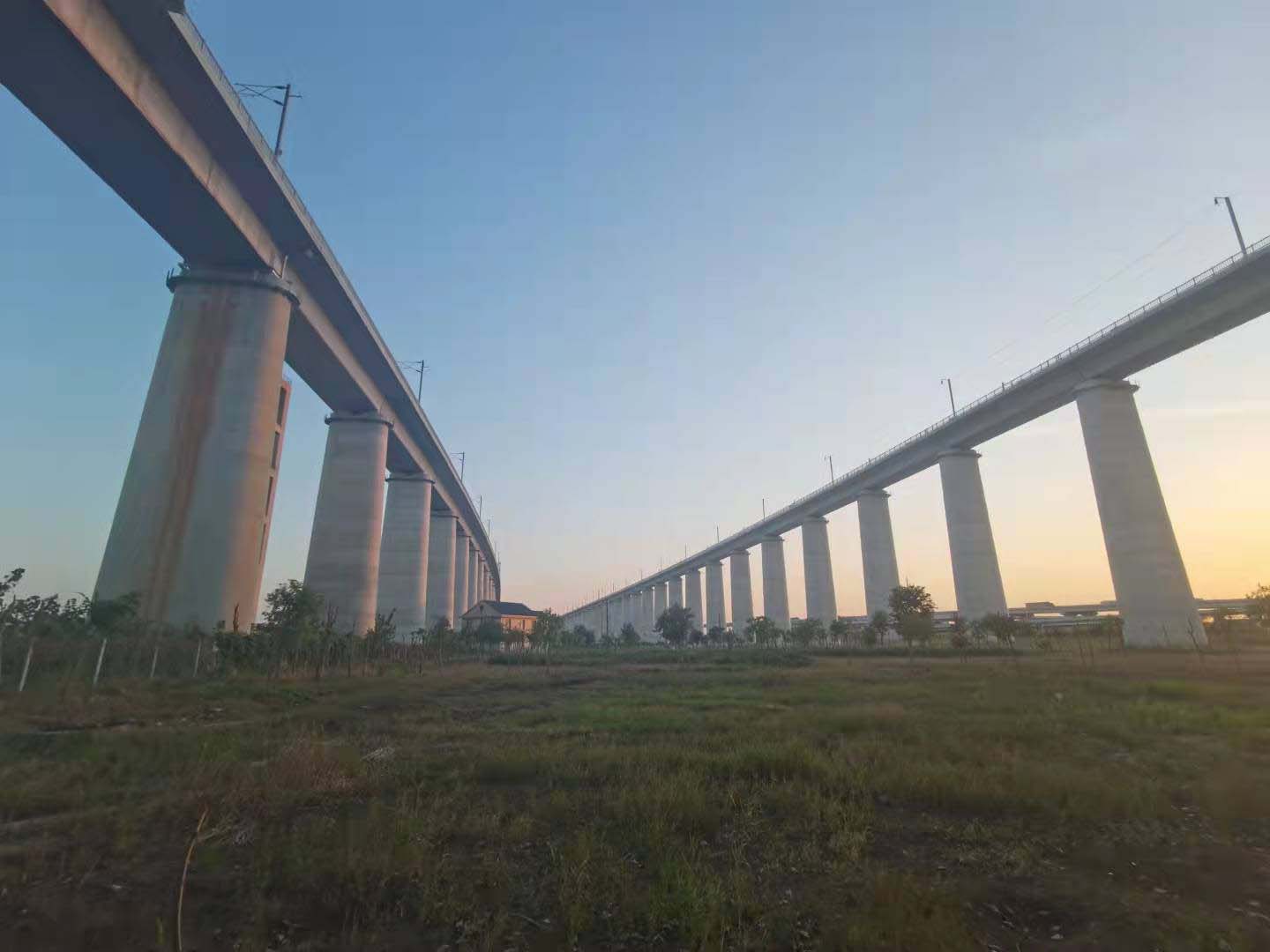

Dinner is over, cigarettes are smoked outside. In the background we see the many pillars that carry the Tonghu railway (通沪铁路) which was opened in 2020. Every five minutes a bright-lit train whizzes passed at two hundred kilometers an hour, leaving or entering Nantong, from or to Shanghai. The wife of someone’s younger brother mumbles: “It stops at 11 o’clock, and starts again at 6 o’clock in the morning.” The two highspeed rails are alien-like in the landscape, dwarfing the houses. To name it alien-like is not an exaggeration; they come from another world, a wholly different China than when the houses here were built.

One uncle commends how rural area has fresh food, space, freedom. The city has none of that. It’s full of people and stressful. But that gloomy vision he describes is the future they will all share.

Every year, the city swallows up more land and whatever is on it, and the biggest gulp is coming within a few years, when the whole area will be cleared for industrial buildings. Everyone knows, the question is just went it’ll happen. But the prospect is nice: they may be compensated with two or three houses in the city. But not necessarily all in the same area.

I ask and wonder whether everyone — when they no longer live together — will still get together for such dinners during such holidays? And although they say yes, I still wonder. More than anything, it is this place that binds these people together, the place they have grown up, the place they return to, once or twice each year.

It is the big question of modernization. Modernity is a taxi-ride hailing app, fast-food delivery. Money can summon a waiter, but friends will share a table with you and drive you home.

Which is the way forward?

Opinions will vary. In either case, when all here is demolished there will be no way back.