(Originally posted on Seventy-Magazine.com)

With 300 million rich Chinese consumers, China’s takes an 8.9% share of the global luxury market — although it’s probably more if you consider Chinese tourists who buy luxury products outside of China. On the surface, luxury advertising in China is similar to that in the West. There are all the global brands with similar faces and similar visuals with golden gradients with serif typography — but important subtleties apply.

Young women & men

China shed its Maoist past 40 years ago, but the economy really kicked in 20 years ago. As such, average Chinese millionaires are only 39 years old, 15 year younger than the global average. Chinese billionaires are 6 years younger than US billionaires. This causes some weird statistics, such as that the ultra rich of China die at the average age of 48 years old — which looks eerie, but there simply aren’t many old ultra-rich Chinese. Thanks to China’s one-child policy there’s the ‘fuerdai’ — children of China’s nouveau riche — the first generation of trustfund kids. I’m using these statistic handles, but of course the luxury market is much bigger. But it does prove that luxury buyers in China are young, often 25-35 year old.

Globally, women spend more on luxury products — and you’d expect the same in China, especially since 30% of its millionaires are female (above the global average). But men are equal spenders in China, explained partly by the fact that men buy both not only for themselves, but also for other men, since gifts is a business-lubricant in China.

Modern taste

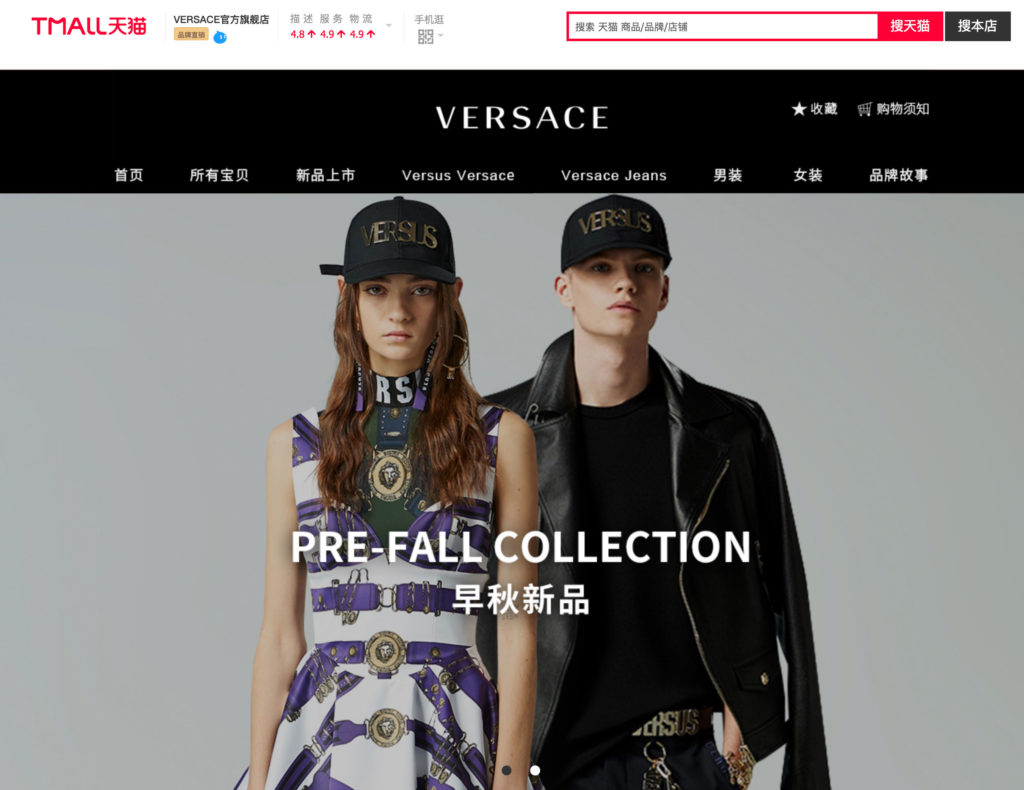

Because audiences are younger, shoppers are more educated, less conformistic, and more individualistic than luxury shoppers elsewhere. As such their choices are often less formal, and they often choose less classical luxury brands. This is not to say that classic Gucci bags aren’t selling — but millennials want less off the ‘same old bling‘. Online storefronts, such as Mercedes-Benz and Versace, are very modern in appearance.

The boundaries of ‘luxury’ are somewhat fading. Premium streetwear and athleisure is worn for looks, rather than sports, and the segment is growing fast with a 12% year-on-year growth. And in its wake, successful hybrid brands have emerged. Particle Fever sits at the crossroad of fashion, tech, and fitness, differentiating by selling a minimalist and futuristic look. Maia Active‘s products are tailored to female Asians, whose bodies are slimmer and less curvy than Western women. Brands like Supreme and Balenciaga hit the sweetspot of luxury and street style, while Li Ning is riding the retro wave. Lululemon appeals to yogis. Lane Crawford works with many Chinese designers.

If you think labelling streetwear or athleisure brands as ‘luxury’ is weird, think about the following: Nike now sells shoes from $55 (the Air Monarch) to $720 (the HyperAdapt) — and it sells $100 sweatpants, just like Ralph Lauren. In 2016, it overtook Louis Vuitton as the most valuable apparel brand. The video for Kenzo World — selling 75ml at $99 — may not have been made for China, but it’s an apt display of the direction the luxury market is heading in. Modern and young, individual (away from the crowd, the spotlight), while remaining premium (hence the gala dress). Burberry just redesigned its logo for a much more modern look.

And it’s not just tastes — it’s also behaviours that are more impulsive and digital. The sheer size of the market has prompted specific luxury e-commerce websites such as Secoo, Mei, Meici, Shangpin, 5Lux and iHaveU. These websites not only act as digital magazines and editors in selecting modern stylish products, they also reassure Chinese consumers of not buying counterfeit products.

Gifting

In the West, one would spend time on a gift for a loved one, writing a poem or making a painting, or carefully selecting a meaningful item, such as a CD with the songs from when you met. It’s the thought that counts. But in China, financial sacrifices matter. Love is money, and Chinese often leave the pricetags on gifts — a taboo in the West, as is asking about the price. But in China, buying someone something expensive proves you feel for them.

Showing off

Luxury products are so important to some youngsters that they spend one-fifth of their incomes on luxury, saving months for a Gucci bag or iPhone. Equally, it’s worth sitting hours in a traffic jam every day, just to show you drive a new BMW. For many young Chinese — especially those who come from lower tier cities — wearing luxury clothes is a showcase on how far they’ve come.

‘Mianzi‘ (or ‘face value’) is an important aspect in China’s group-oriented society, and luxury products are an easy (if not expensive) way to gain it. This is partly why lingerie labels such as La Perla and Agent Provocateur have failed in China: it’s much harder to parade your status with products nobody sees (except your partner, maybe). It’s the high visibility of jewellery as well as everyday luxuries such as Starbucks that drives desirability. Wealthy Chinese are much less shy about flaunting their wealth than equally well-off in other countries.

This in itself is a huge contradiction. For millennia, Confucian frugality was deeply ingrained in Chinese society. Even today, consumption accounts for just 39% of China’s GDP, significantly lower than for most Asian countries, and less than half the rate in the United States (83%). On average, Chinese save a quarter of their income, largely because safety nets that Western consumers have (such as medical care) don’t exist in China.

The government is not entirely happy the public display of wealth. It banned the word ‘luxury’ from billboards in 2011 to ease public concerns about the widening wealth gap. The appeal of luxury products also made it easy to bribe corrupt officials. Bloggers were keen to point out officials who wore wristwatches which they could never have afforded on their salaries — and monthly sales figures of the expensive Baiju liquor were mockingly been described as national corruption index. The Economist points out the irony in the article ‘The Middle Blingdom‘: “Mao Zedong would not have approved, but his next of kin ignore his frowns and happily spend the banknotes that still depict his face.”