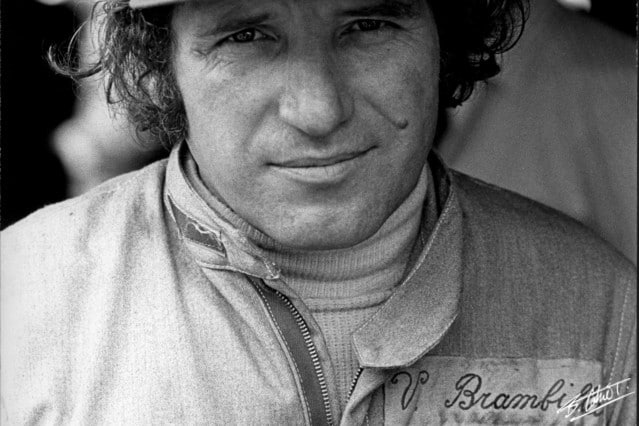

1976 Germany German Grand Prix – Copyright © The Cahier Archive

“Car good, Vittorio good.” Vittorio Brambilla spoke Italian and French, but little English. At the age of thirty-six he was a former mechanic and brought to Formula 1 as a driver by sponsor Beta. Nobody expected anything of him, but days would come where ‘the Monza Gorilla’ stunned the Grand Prix scene with his all-out sense of maniac driving.

Vittorio and his brother Tino grew up in the town of Monza. The brothers would ride the Moto Guzis from their father’s dealership to school and work, and the story goes that they once took the blind turn that led into the parking lot of the dealership at extreme high speed. To do this, it was vital their father had opened the heavy wooden door of the lot. That morning Papa Brambilla forgot to do so, and the brothers wrecked their bikes. (The first of many, for both of them.)

Both brothers began racing motorcycles. When Tino switched to four wheels, Vittorio became his mechanic. There’s an anecdote of a private test for Tino at Monza, when Vittorio, from the pits, couldn’t hear an engine noise, so he sent out a mechanic with a jerrycan. Tino had indeed ran out of fuel, and with the jerrycan emptied in the car, he continued, giving the mechanic a ride back to the pitlane. Tino drove away but quickly forgot he was carrying someone, going flat-out. Upon arriving back in the pits after his stint, everyone wondered where the mechanic was. He was found, an hour later, in Parabolica’s gravel.

Tino eventually reached Formula 1 with Ferrari, although, from two weekends, only qualified once. He would never start that race as he had to give the car for Pedro Rodríguez.

Vittorio, all this time, stood by as Tino’s mechanic, but eventually started racing for himself. First in karts, then he raced Tino’s Birel in Italian Formula 3, where he claimed the title in 1972. He continued in Formula 2 where he made a name for himself as an all-out driver. A competitor, John Bisignano, later recalled: “The only reason I hold the Formula 2 lap record at Jarama, is because ’the Monza Gorilla’ chased me for the entire race!”

In 1974 he was promoted to a Formula 1 seat with March with funds from sponsor Beta. Vittorio proved to be as quick as his teammate Hans-Joachim Stuck, although more accident-prone. He was on course for points in Sweden, until his engine failed, but he collected his first point in the Austrian Grand Prix.

Trackwalk for the 1975 Spanish Grand Prix, Brambilla and Peterson in overalls – Copyright © The Cahier Archive

In 1975 he took the lead during the Belgian Grand Prix, and qualified in pole position at the Swedish race at Anderstorp. Years later, a mechanic admitted to flinging the pitboard across the timing beam shortly before Vittorio arrived, gaining him valuable tenths. Regardless the iffy pole, Brambilla led the first sixteen laps on merit, before, again, he had to retire his car.

The March was no frontrunner. Especially its brakes possessed little stopping power, a flaw made undone by rain. That of which, came plentiful during the Austrian Grand Prix that year, at the Österreichring.

Beneath thunderclouds, the race started. Several cars span out, but Brambilla, from eighth on the grid, shot through the spray into the lead as he overtook Niki Lauda and James Hunt. The race was subsequently stopped halfway due to the weather. Brambilla slithered across the line in the lead, and took both hands of the steering wheel to celebrate. He lost control and crashed into the barriers. Some teams prepared for a restart, but because the race was flagged with a checkered, instead of a red flag, it couldn’t be restarted. Vittorio received half points, but didn’t care: the oldest driver in the field had won his first Grand Prix.

He remained with March for the 1976 season, which had grown to four drivers, but Brambilla would only score a single point at the Dutch Grand Prix. Again, the car proved to be unreliable, but Brambilla was equally fallible. The number of wrecks piled up, but Brambilla always escaped unharmed.

A journalist once wrote a spoof report on Brambilla, joking that nobody had seen Brambilla since early practise for the German Grand Prix, and that his car was found in a deep gorge with a note attached to the steering wheel, reading something like: “I don’t think you are able to retrieve it from here, so I went home”. In another magazine, a photo of Brambilla, driving the orange March, was captioned: “Preparing to go where no man has gone before, the Monza Gorilla prepares to write off yet another March.” Another, with Brambilla’s March running without a nose, read: “Carrying on with relatively little damage (for him).”

At the end of the season, March stated they would be scaling back their operations, as they found it difficult to prepare four cars for each race. Chief designer Robin Herd mocked it should have said ‘repair’, not ‘prepare’, thanks to Brambilla.

1976 Belgium Grand Prix – Copyright © The Cahier Archive

He switched to Team Surtees, and brought sponsor Beta with him. A mechanic of the team recalled the Monaco Grand Prix: “During the race, Vittorio was gaining on his forerunner, but suddenly he’d lose a lot of time. This happened several times. After the race we questioned him, thinking that maybe there was a problem with the car. He replied he had worn a new balaclava which, during the race, would slowly fall down, obscuring his vision. The delay was due to him slowing down as he opened his visor and pushed it back up with his fingers. Then it would happen again in a few laps.”

Brambilla would score points on three occasions in 1977, and once in 1978, although that season was cut short during that season’s Italian Grand Prix. In the carnage that killed Ronnie Peterson, a tyre hit Vittiorio’s helmet. Left in a coma, it took a full year for him to recover. Afterwards he raced four more grand prix, but he was never up to his old self. Brambilla retired at the end of 1980.

The start of the 1978 Italian Grand Prix, the carnage that killed Ronnie Peterson. In the left of the picture is Brambilla’s car, assaulted by a loose tyre. – Copyright © The Cahier Archive

He owned a Formula 1 memorabilia shop and his own garage in Monza. Occasionally he drove the medical car during the Italian race. Sid Watkins remembered him asking: “Professor, how close to you want me to stay with the cars at the start?”, to which Sid Watkins replied: “Vittorio, I don’t mind close, but I don’t want you in the lead at the end of the first lap.”

In 2001, while mowing the lawn, Vittorio Brambilla died of a heart attack, at the age of sixty-three. Of those who remember him, some think of an enthusiastic amateur racer who fluked a victory, but Brambilla wasn’t a flash in the pan. He ran towards the front on several occasions, and never in the best of material. Brambilla was one of the greatest characters of the sport, an advocate of all that life’s good, and above all, a fervor for racing.

Vittorio had kept one piece of memorabilia for himself, adorning the wall of his garage. He had personalised it twice – once with his name in pen, the other with the cracks from the impact with the Austrian guardrails. It was the damaged nose from the March he drove at the day of his sole victory.