Ahead of the 1958 season, the team of Ferrari fielded three young and talented drivers, causing the Italian press to call them ‘La Squadra Primavera’ – The Spring Team. They were Luigi Musso from Italy, and Mike Hawtorn and Peter Collins from the United Kingdom. Yet, in less than 12 months, all three would have lost their lives.

Peter Collins was born in 1931 as the son of a well-known garage owner, in Kidderminster, England. At 16, after being expelled from school, he became his father’s apprentice, and at 17 he got a Cooper Mk II; a cheap and lightweight racing car. Peter practiced on airfields and made his racing debut a year later, at the 1949 Goodwood Easter Meeting. He retired after leading part of the race.

The following years, Collins combined hill climbs and circuit racing, quickly moving through heavier and faster classes. While his early form was variable, Peter quickly learned and started winning races more regularly. For the 1952 season, he joined the British Formula 2 team Hersham and Walton Motors.

Then something unexpected happened; Alfa Romeo withdrew from racing, prompting the FIA to fear that Formula 1’s grid would be too small. The federation then decided that the 1952 season would be run under Formula 2 specifications to allow more teams, such as HWM, to race. Peter Collins was promoted to Grand Prix driver, at the young age of 20.

Start of the 1953 French Grand Prix – © f1-photo.com

Compared to Formula 1’s racing elite, the HWM team was terribly underfunded, their car underpowered and fragile. Despite this setback Collins sensationally made his debut at Swiss Grand Prix at Bremgarten, qualifying in 6th, retiring from the race with a broken halfshaft. Much of the season would follow the same story — flashes of speed coupled with mechanical issues — as would 1953. After driving for Vanwell in 1954, and BRM and Maserati in 1955, Collins had only finished 4 of his 12 starts, and was still without a single points finish.

Fangio & Collins – © f1-photo.com

But Enzo Ferrari had seen enough, and in 1956 he partnered the youngster with Juan Manuel Fangio. Under Fangio, who had claimed his third title in 1955, Peter learned and matured as a driver, resulting in victories in Belgium and France, causing him to lead the championship. The 1956 championship went down to the wire, with the title decider at Monza, which yielded one of the most remarkable acts of sportsmanship in the history of racing.

To clinch the title Collins had to finish ahead of Fangio, but the Argentinian retired early in the race with a broken steering arm. Luigi Musso, also driving for Ferrari, was ordered to hand his car over to Fangio, but the small and stubborn Italian refused. Collins was well on his way to become Britain’s first Formula One World Champion when he stepped out of the car during a routine pitstop, handing over the wheel to Fangio. “My time will come”, Collins said. While Stirling Moss won, Fangio finished second, sharing the points with Collins, ensuring Fangio his fourth title.

Enzo Ferrari was brought to tears by Collins’ act of sportsmanship. That same year, Ferrari had lost his only son, Dino, but from there on, Ferrari and Collins would develop a father-and-son like relationship.

Collins lived near Maranello with his wife, Louise, an American actress who he had married only a week after meeting. The story goes that Collins and a fellow driver were sunbathing at a pool in Monaco, with Louise in the middle. Collins leaned over and whispering to her so that the other driver would not hear, asking her to marry him. She smiled and whispered back “yes”.

The two married in the beginning of 1957. Meanwhile, Collins was joined at Ferrari by Mike Hawthorn, also from the United Kingdom. Collins and Hawthorn quickly developed a friendship and, given the perils of the sport of that time, decided to split their winnings together instead of pushing each other too far. That arrangement resulted in a fierce rivalry with Luigi Musso, the Italian who was also driving for Ferrari. Musso’s then-girlfriend recalled that “the Englishmen, Hawthorn and Collins, were united against him. I hated them for it.”

Not that it mattered, as the 1957 challenger by Ferrari was overweight and underpowered. After Fangio left for Maserati, the Scuderia failed to win a single race. To make matters worse, Eugenio Castellotti and Alfonso de Portago both died in non-F1 events.

Collins in the Ferrari Dino 246 during the 1958 Monaco Grand Prix – Copyright © The Cahier Archive

Collins, 1958 Monaco – © f1-photo.com

Yet the 1958 season proved even more poisonous. The antagonism between Musso and the English drivers continued to brew, and around the same time Musso amassed a massive debt. He had shipped a thousand American Pontiacs to Italy, to sell at a profit. Yet it had never occurred to Musso that the Pontiacs were way too big for the twisty Italian roads, with their brakes far too weak, rendering the cars unsellable. Winning the French Grand Prix was thus pivotal to Musso, as it yielded the most prize money of the whole season. The new Ferrari, which had collected five podiums in four races already, was definitely capable of such a result.

On the evening before the race, Hawthorn, whether joking or not, said to Musso he and Collins would ensure the next world champion would be English, not Italian. Musso was furious, and his anger couldn’t be contained. From the start of the race Musso was trailing Hawthorn who was leading, and the Italian tried to pass at the slight bend just before the hairpin but, unlike any time before, he took that corner flat-out. The scarlet Ferrari slid, overcorrected, hit a ditch and launched ten meters into the air. Hawthorn went on win the race, as Musso died that night in the hospital near the track.

The British Grand Prix was held two weeks later. Collins took the lead from the start and sped to victory, followed by Hawthorn. Louise recalled that “when Peter won the British Grand Prix in 1958, it was a perfect day. After I remember Peter started saying something like, ‘If anything ever happens to me’, and I said, ‘Oh, shush!””

Collins en route to victory at Silverstone, 1958 – © f1-photo.com

Then came the German Grand Prix at the treacherous 73-corner circuit of the Nordschleife. On the morning of the race, Hawthorn barged into the hotelroom of the Collinses’. While Louise was awake, he saw Peter sleeping. Hawthorn wrote in a memoir; “I remember looking at Peter and thinking to myself, ‘he’s the one that won’t die.’” But fate planned otherwise. When the Grand Prix started, it was Stirling Moss in the Vanwall who took the lead, yet he retired on lap 3 (of 15). It was then a three-car train of Tony Brooks’ Vanwell and the Ferrari’s of Collins and Hawthorn. The cars fought for the lead, howling through the German forest. Then, disaster struck. Collins was right behind Brooks when he got off line at Pflanzgarten. His left rear wheel hit a slight embankment. The Ferrari shot in the air, throwing Collins out.

Hawthorn thought Collins would be alright. When his clutch failed, just over a lap later, he went to the spot of the accident and collected his helmet and gloves, which where both unscratched. Meanwhile, someone told Louise that Peter was walking back to the pits. But when Hawthorn arrived in the pits, he had heard the news. Then Louise knew it too; “When Mike came back to the pits, he turned around when he saw me. That’s when I knew something bad had happened.”

She was then told the situation was much dire than she’d realised. Collins had landed head-first on a trunk and was being flown to a hospital in Bonn and she was taken there by car. Upon arriving, a doctor brought Louise to the phone; it was her dad from New York, who wanted to be the one who told her that Peter had died on his way to the hospital in the helicopter.

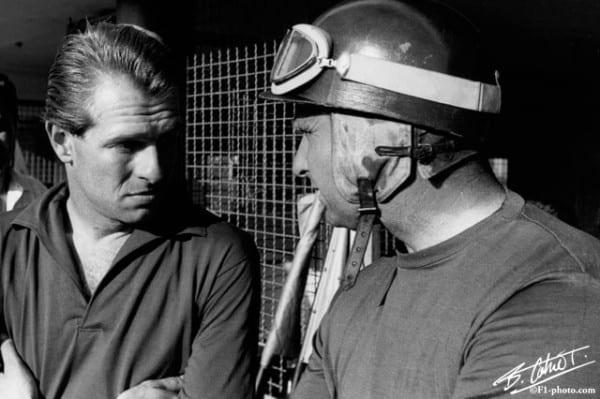

Hawthorn and Collins – © f1-photo.com

All the drivers were in shock, not least Hawthorn, but Collins and him, who called each other ‘mon ami mate‘, had made a pact. If one would die, the other would keep racing. In honour of that, Hawthorn finished the season. He finishing all remaining races in 2nd place and clinched the title, becoming Britain’s first World Champion.

Even though Hawthorn decided to immediately retire from the sport, he couldn’t escape a tragic fate. That winter he was driving Jaguar when he saw the Mercedes of Rob Walker, manager of the racing team with the same name. In wet conditions the two raced down the English highway. Hawthorn passed Walker in a right kink but clipped a bollard. He span, hit a lorry, crashed into a tree, and succumbed on the spot.

‘La Squadra Primavera’ was no more. Castellotti, De Portago, Collins and Hawthorn had all died, as would Wolfgang von Trips, driving for Ferrari, in 1961.

In this era of the sport there was a lot of critique for it’s brutality. After Collins’ death, a journalist wrote for Motor Sport: “Peter died gallantly, driving a fine car to its limit of speed, and beyond. Musso died likewise. These accidents enhance the stature of the racing driver, who faces danger fearlessly with open eyes. To use them as a weapon with which to bludgeon a clean and healthy sport is futile indeed.”

That paragraphs shows the spirit of that period of time, built on two world wars, in which lives mattered little. But the story of Peter Collins lives on, not least with Louise. She went back to acting, and after a long career she still looks back most fondest on her short time with Peter, who she still describes as ‘the love of her life’.

Peter & Louise, Monaco 1957 – © f1-photo.com