Before moving to Shanghai in 2018, I went through a dozen books about China to prepare myself. Several of those books belonged to the genre of ‘Westerners in China who write a book about their friends’, such as ‘Street of Eternal Happiness’ (Rob Schmitz), ‘Wish Lanterns’ (Alec Ash), and ‘Young China’ (Zak Dychtwald). It’s an easy recipe that’s hard to botch, but to read so many of them becomes tedious. Even if the seasoning changes, the main ingredients are often the same: The pressure to marry, stress about money, and in each book the search for one’s own identity in a changing China, caught between the pressure from parents as well as an internal desire to walk your own path. It’s tedious to be lectured about the same history again and again — the turbulent 60s and 80s, the opening up of China in the 80s, and rapid GDP growth. The same terms make their way to you everytime, explained in laymen’s terms: leftover women, wangba (internet bar), daigou (purchasing agent), etcetera. It’s like they copied each other’s homework.

And when I started learning Chinese at GoEast, I heard many fellow students mention Peter Hessler with reverie, but I wasn’t motivated to read it, maybe because they were carrying HSK4 books which put them in a whole different league than me, having just started with HSK1. Only in my third year in China did I read his book ‘Oracle Bones’, from which I loved the endless stories and stories, woven into a bigger narrative of old and new China.

Hessler transcends the genre of a foreigner in China simply writing about his friends. He’ll sometimes cross that divide of being a foreigner to really be among Chinese people, getting their stories beyond an anecdotal level. It also helps he lived in Fuling, and not Shanghai or Beijing.

I thought ‘River Town’ would be slightly less good than ‘Oracle Bones’, because it’s Hessler’s earlier work. It stands to reason a writer gets better over time, no? But to me, River Town is fantastic, a better book. It’s less ambitious and purer as a result. Stories don’t get presented with statistics or connected to a bigger theme or headlines, it’s just Hessler and the people of Fuling, caught between the mountains and the Yangtze.

Maybe the reader has changed. I understand China better than when I read Oracle Bones, and I also see a reflection of myself in the story. It’s now my fourth year in China, and I see all those things I read in those dozen books before coming to China. I realize those books were kinda right, but only when you live here and experience it yourself do you fully understand how the pieces fit.

It’s great that Fuling has been documented like this before the flood from the Three Gorges Dam. Not just the houses or the White Crane Ridge, now all gone — but also the people and their thoughts and feelings towards the changes. And I see within this the area in which I spent a lot of time in rural Nantong, an area like Fuling threatened with destruction.

While reading River Town though, I often feel slightly embarrassed on how well Hessler can notice these things and I cannot, and that only after reading his words I too notice it.

And many of these observations still ring true today. (The book feels very timely and timeless at the same time.)

The air pollution is gone but noise is still here. The problems with money and marriage, the flaunting, the Christian church, and people’s identity, is partly made by how others view you (Everyone is someone’s wife or husband, daughter or father. Everyone is in relation to everyone), and yet young people are trying to break free and etch an identity for themselves. And even the experience of being a foreigner in China is still very similar, even if perhaps a little less extreme.

I also see myself in Hessler’s Mandarin learning journey. The signs and banners that slowly become readable as your Mandarin progresses, the conversations that open up.

I know which Chinese words were used in those conversations, and even the political discussions with his Chinese language teachers are familiar to me. Peter has foreign magazines, I have a VPN, and for fear of being a pedantic foreigner on Chinese topics, I often swallow my answers discussing topics like “Where did covid come from?”, or Taiwan, or whether minorities need the help of the government. (Photo from 会通5.)

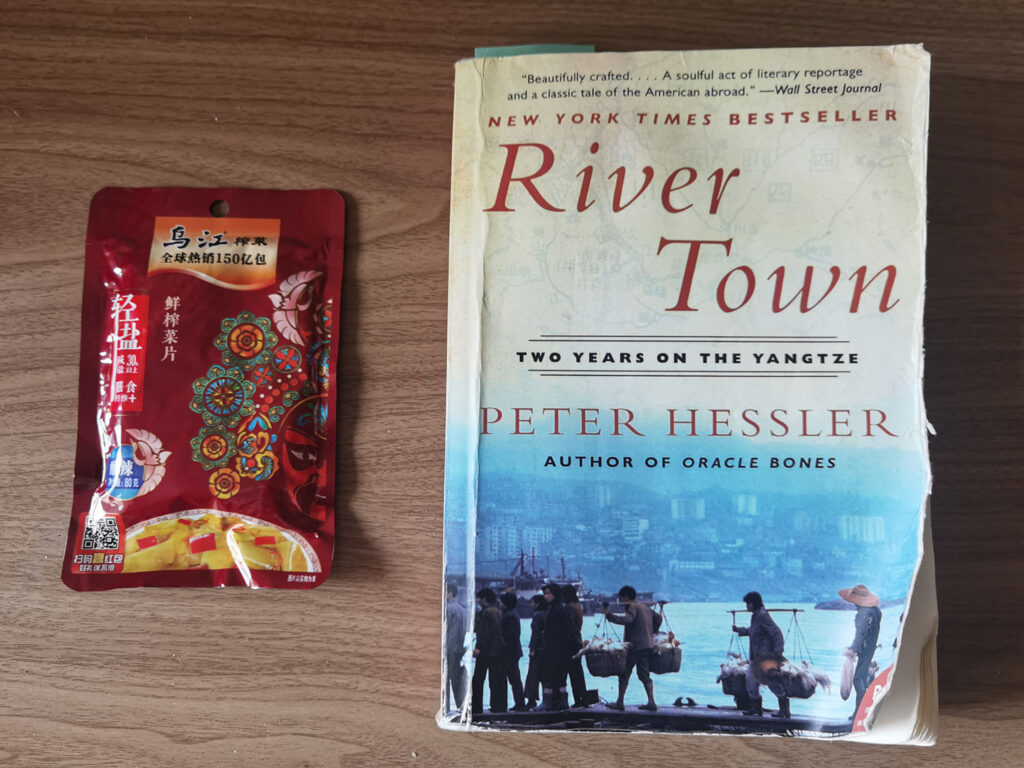

Hessler described pirated copies of the movie Titanic. It’s only ironic I bought his book on Taobao, but I’m pretty sure it’s an e-book that’s printed out because page numbers are missing. Here with Fuling’s famous pickled mustard tuber next to it, which I bought after reading it so often in the book.