Chinese characters allow for elegant naming. Just take a character from each destination and add what it is. The highway from Jiading to Songjiang: 嘉松公路 (JiaSong Highway). The bridge from Suzhou to Nantong: 苏通桥 (SuTong Bridge). And there’s the HuiHang Ancient Road (微杭古道). The Hui is from Huizhou (徽州) in the Anhui province, the Hang is from Hangzhou (杭州) in the Zhejiang province. In English it’s sometimes called the Hui Hang Caravan Trail, because that’s what it is — an ancient merchant trail.

The original trail must have been over two hundred kilometers, if not longer or part of a bigger system (like the Silk Road), but the trail that carries the name today is only a twenty-kilometer trek from Jiangnan Village (江南第一村) to Yonglai Village (永来村). And you cross province borders in the process.

To get to Jiangnan, I took the high-speed train from Shanghai to Jixi (绩溪), which is one stop earlier than Huangshan (黄山), and the last part a taxi driver named Zhang (章) sends me there, in his brand new BYD (比亚迪). He says he has lived his whole life in Jixi.

“Have you seen lots of change in the area here, in the last decades?”

— “Not really, still the same. These roads were all here already. Maybe a bit narrower.”

“What about the high-speed train station?”

— “Ah yes, that influence was huge. Also because lots of tracks come through Jixi. It has brought lots of tourists from all directions. [[This is visible; the station has eight platforms, a lot for such a small city.]] All year round. Also some foreigners sometimes. But most bring translators. Although the last two years a lot less, because of covid.” Zhang has walked the HuiHang Ancient Road in the past: “But only halfway, then I went back. But I guess that still counts as full distance.”

I’m starting the hike at 08:00 because today is set to be 39°C (102°F) . The new ticket office is still under construction and I’m the first to buy a ticket, and my race starts. Not against time, but against the temperature and the angle of the sun. There’s still plenty of shade now, but at noon?

The ticket lady gives me good advice: “Don’t go all the way to Yonglai Village. The last five kilometers are a bit boring, and you’ll reach the other side of the mountain — a taxi will have to go all around the mountain, over a hundred kilometers instead of thirty. And the drivers there will only give you outrageous prices, like five hundred RMB. Turn back or south instead.”

From the start, I’m instinctively taking photos in portrait rather than landscape. Unlike Huangshan or other mountains, the view isn’t from the mountain; here, the view is the road itself. And this road is laid out for practical purposes. It does have elevation change, but it doesn’t cross peaks or viewing points. Like the river, it seeks the path of least resistance, the fastest way to Hangzhou, wedged between two cliffs.

Every kilometer or so there’s a stand with a senior selling water, and all of them are almost begging to buy something — citing that with covid, there have been almost no travelers nor income in the last two years. The prices are fair but I’m already carrying three liters of water in my backpack.

In the end, I bought a bottle of Pepsi from a lady, but it was without fizzy bubbles, betraying its age. Later I bought a bottle of water, but a few kilometers later discovered it was already opened. (Refilled or opened by mistake?) I drank it anyway, I had to — before I’d resort to drinking from the river.

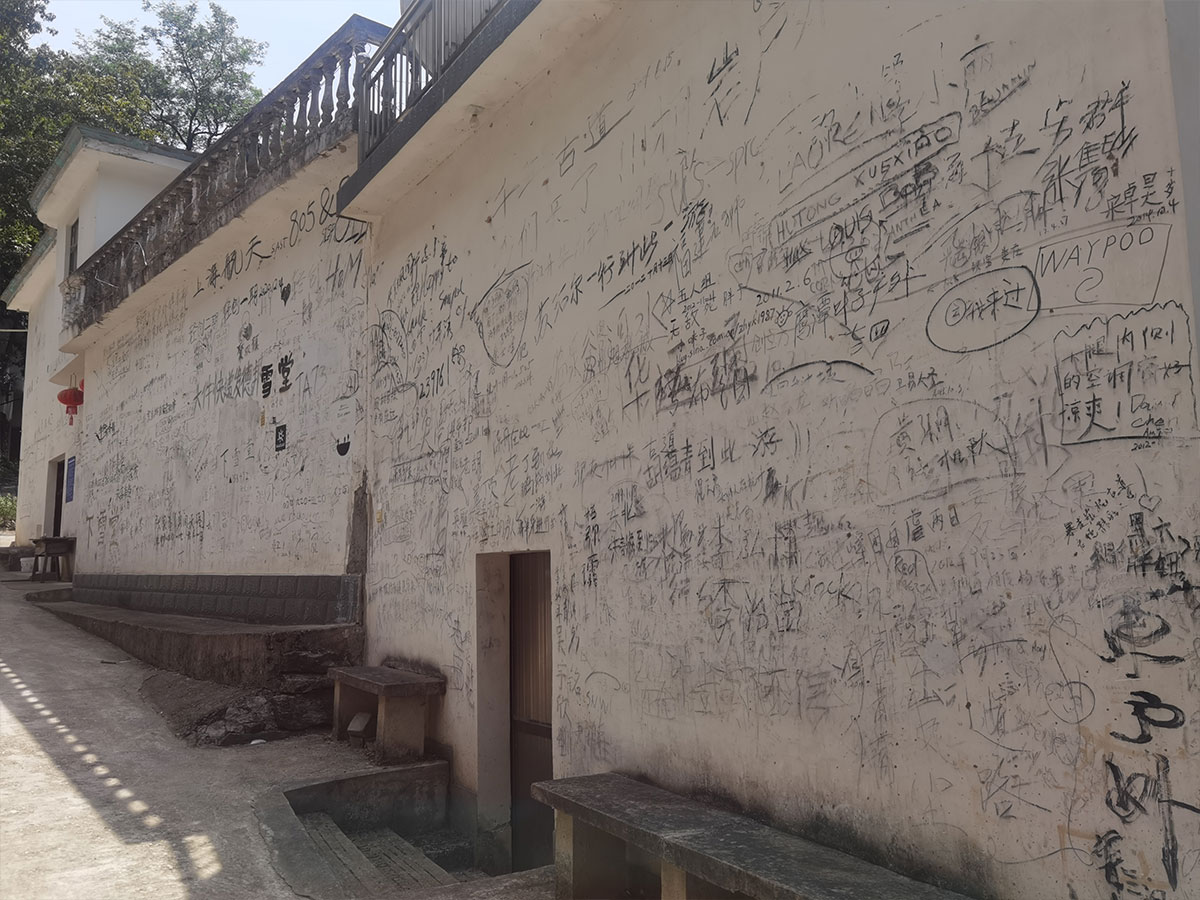

One hotel has names of travelers on the wall, including lots of foreign names: “But the last two years, the foreigners aren’t here anymore”, the owner says.

The summer has been relentless in the area, just like in Shanghai — although 40 degrees in the mountains isn’t as warm as 40 degrees in the concrete city.

These hundreds of creeks eventually flow into the Xin’an river (新安江) and eventually Qiantang River (钱塘江), passing Hangzhou and into the sea. But the main river runs low — almost dry — and one of the water-selling seniors says it didn’t rain a lot lately, or the whole year actually. “A sign of climate change?” I ask. “Maybe.”

I reach “蓝天凹”, which is the best place name I’ve ever seen: Blue Sky Indent. The character 凹 looks like the mountains here, and the shape it leaves out is a blue sky (with some clouds). I follow the ticket lady’s advice and turn south instead of marching on.

This path goes back in the direction of Jixi, but it’s the long way back — through the Yanshan Grand Canyon (鄣山大峡谷). But like the HuiHang Ancient Road, it’s a road still in use, not just to sell water and coke to tourists, but there are crops being grown as well.

I love this all for the road’s sake. This is the road ancient merchants took. But I’m also reminded of the hikes (Randonnées) my dad and I took in the French Pyrenees, now almost twenty years ago. I haven’t seen him in over three years now because of China’s zero covid policy. This road feels like the roads I’ve read about in youth novels, or the one where Frodo took the ring. And for all my steps, lizards dash out of the way I’m thinking of my brother, how all that time ago, we were trying to catch lizards in France. We never succeeded, only ever caught their tails.

My dad, my brother. Old foreign names on the wall while they’re no longer here, a hot climate and a river that runs dry — zero covid in China and the tourists that aren’t coming, youth memories and all of that.

So you see, roads are really for connecting things.

Video (in Mandarin):