This morning I read Arthur C. Brooks’ article “Your Professional Decline Is Coming (Much) Sooner Than You Think” on The Atlantic. It’s packed with way more than you’d expect from a long article, and since I wish to absorb it all, I’ll leave a summary below here.

—

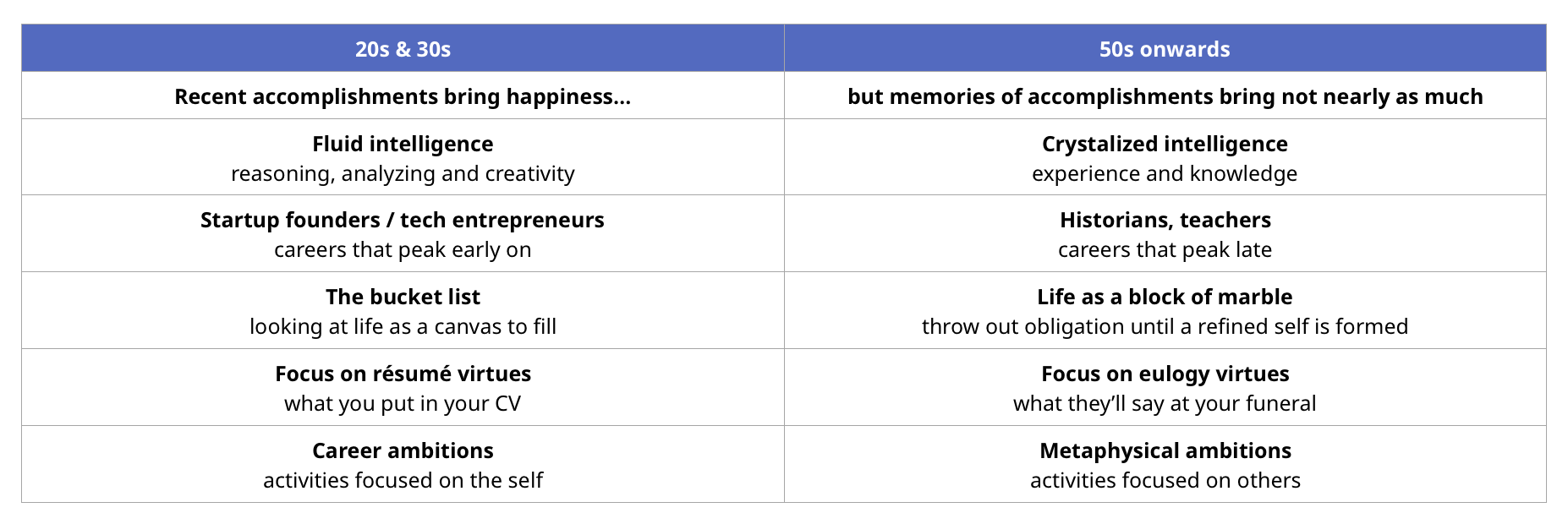

Memories of accomplishments don’t bring nearly as much happiness as current accomplishments. This is important for when we age, because our achievements inevitably halt. Because if you reach professional heights and are deeply invested in being that high up, you suffer mightily when you inevitably fall.

Now it gets most interesting with these two terms:

1) Fluid intelligence, named to describe reasoning, analyzing and creativity — which is highest in young adulthood but diminishes in one’s 30s and 40s.

2) Crystallized intelligence — which comes from experience and knowledge, which builds and builds until it declines very late in life.

Careers that depend on fluid intelligence peak early on, while crystalized experience peaks later. Startup founders and tech innovators peak early, historians and teachers peak late in life.

Brooks uses this to explain what he calls the ‘reverse bucket list’. After growing older and accomplishing more, there comes a peak of success and after that it may be time to stop looking at life as a canvas to fill, but to see it as a block of marble to ship away from. “My goal for each year of the rest of my life should be to throw out things, obligations, and relationships until I can clearly see my refined self in its best form.”

If life’s has a hill that sits half way, it should be climbed with résumé virtues, and descended with eulogy virtues. The former is what you put in your CV (Master degree in physics), the latter what they’ll say at your funeral (“He was a deeply spiritual person”). In other words, work for yourself first, then work for others.

Take for instance Darwin, who reached his peak of fame in his late 20s, early 30s, but fell behind as an innovator in later life and became depressed of inactivity. Bach, similarly, peaked before his 40s, but as he grew older he realized his music fell out of taste and became a teacher instead. He did what Darwin didn’t, and lived a meaningful and grateful life after his peak of accomplishment.

The lesson is here is to be like Bach, and not like Darwin. Decline is inevitable, but misery isn’t.