(Originally posted on Seventy-Magazine.com, and in Dutch on Marketingfacts)

When we think about China, we often reduce nuances to black-and-white absolutes. Either China is a country with oppressed people and smog-filled skies, or it is the juggernaut that will inevitably rule the world’s economy. Neither of these views is particularly useful, and rather than debating what’s good or bad, it’s more interesting to look at how China is different. There are many ways, but one of the most interesting narratives, I think, is comparing the ‘Western’ and ‘Chinese’ schools of thought.

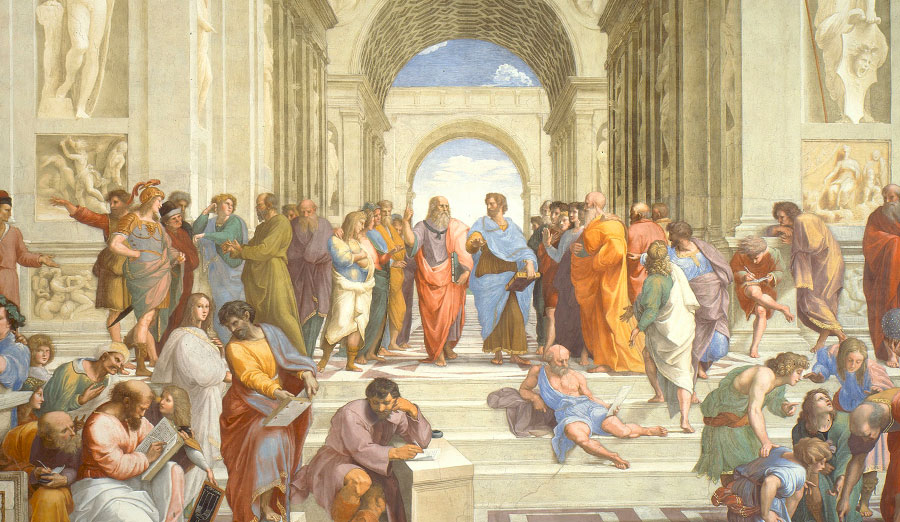

The Western school of thought originates from Ancient Greece. As a territory, it’s hugely exposed to mountains and islands. 10,000 years ago, the Greeks colonized territories around the Mediterranean Sea, and traded with what is now Russia, France, Spain, Liberia and Egypt.

They needed an approach on how to think about this. Categories proved useful. Fur and wool were isolation material, stone and wood were building material. A sheep would be worth this much gold, and a slave would be worth that much grain. Objects had to be taken out of context to be understood and to be valued. Not every slave was equally strong, or all grain equally fresh. Even people were individual. You were not your family, you were free to forge your own destiny. The ancient Olympics are a good example of this.

And so the Greeks believed in rationality and statements of truth to describe the world. Objective truth, or universal truth, as Plato called it. They had to — because they traded with vastly different people. Water is wet and fire is hot. Through reason, something could not be A and Not-A at the same time. This was the result of their economy, which was the result of their ecology.

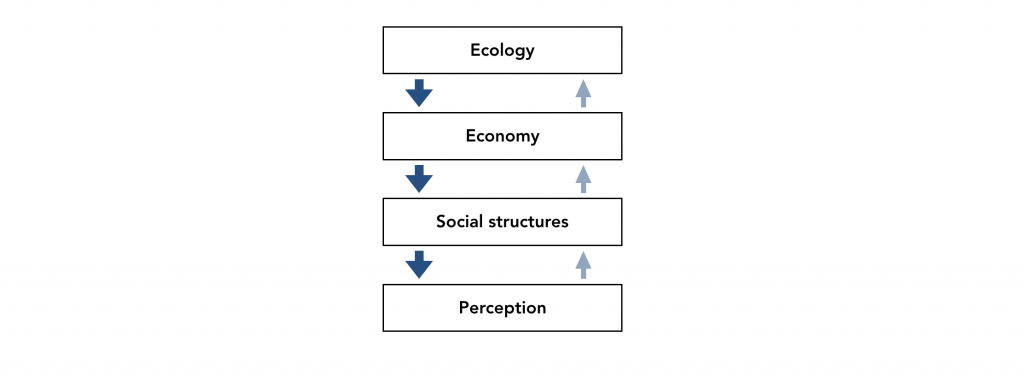

This is how Ecology influences the Economy, which affects social structures and perception. And creates a continuous loop. In the Geography of Thought, Richard E. Nisbett makes this compelling case.

But now look at China. Equally many millennia ago. Totally different ecology. As a country it relied on agriculture and was largely fended off from the rest of the word. Yes, there was the silk road, but unlike a ‘single’ route, it consisted of thousands of routes, and Chinese merchants rarely ventured farther than Persia. As a country, China relied mainly on agriculture, for which it created 24 ‘seasons’, on the lunar calendar, which in Chinese is also called the ‘Rural Calendar’ or ‘Farming calendar’.

And the Confucian school of thought was both the result of a tool of that rural agriculture. Each individual has a role in the family. There was the elder decision maker, the muscle, and the cook. And each family had a role and reputation within the village. That’s how society worked. Respect your elders, have your role. Individuals could be whoever they wanted to be.

So this influenced the way Chinese thought about and saw the world. The Greek philosophers pursued ‘truth’, while in Taoism, ‘truth’ lies in ‘the way’, the middle of Yin and the Yang. Unlike the Greek, they believed in contradiction. A could be true, just like as Not-A. It’s actually in the spirit of the Tao and Yin-Yang that if A is true, then Not-A must also exist. Events and objects do not exist in isolation, but are always part of a bigger whole. The Chinese school of thought relied way more on contextual observation, looking at the relationship between things, rather than singling them out.

While the Greeks celebrated human capabilities in the Olympics, the Chinese saw themselves as part of nature. Individuals cannot change their destiny, nor rise to heroics (apart from the Emperor). In classical Chinese paintings, the landscapes are overwhelming and humans — if there are humans at all — are always shown tiny. But then painters in China did put their feelings into paintings, something Western painters wouldn’t do until the 17th century. Instead, Western painters wanted to paint as realistic as possible. Objective truth mattered.

Modern tests showed that when Western people look at a wall, they see a wall — or focus on a brick. But Chinese will see a collection of bricks. When Western people look at an aquarium, they see a school of fish, but Chinese more perceptive of the shared movements of the fish, which one stands out and which one blends in.

It’s hard for us to believe that people from may perceive reality different than us. This already applied true for a spouse, but what about people on the other side of the world? The ‘Chinese school of thought’ is still very much present in China — even though its agricultural society and its Confucianism are being torn apart by urbanisation and globalisation. Families are broken up when parents stay in their home town, while their kids move to huge cities — where life is much more individual. There, younger generations are exposed to Western media and Western brands and Western ideas about individuality and creativity and expression. ‘Just Do It’ and ‘I’m Loving It’.

But some aspects of the way of thinking still apply. It’s still the collective whole that matters, not individuals. It’s how China is governed. No democracy, which was a product from Ancient Greece. This is how families and businesses work. Community matters, not individuals. Context matters, not specifics. If you go to the doctor in China, they’ll not only ask about your headache, but also about your personal life, if work is going well and if you love your parents, etcetera. Context matters. And Chinese eat their food together, all sharing the same plates.

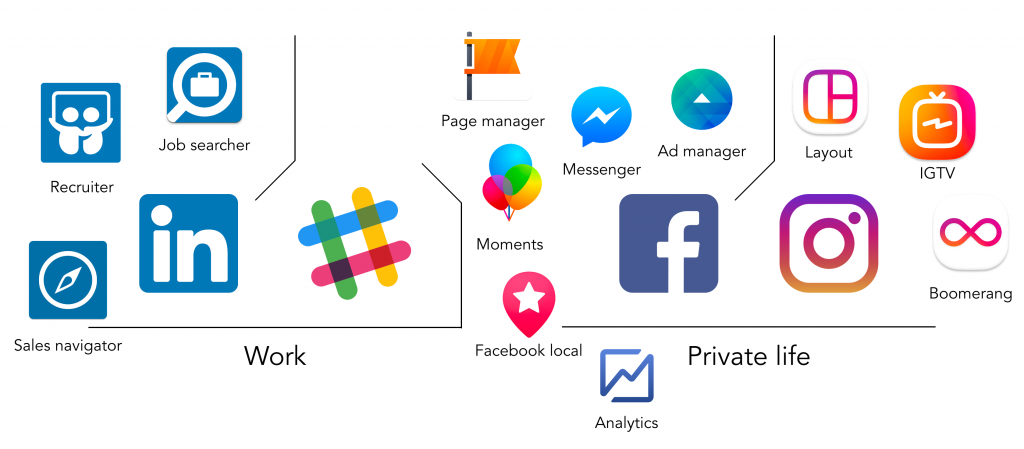

But it gets more interesting when we look at media. In the West we neatly separate social media into work (LinkedIn, or Slack), friends, family (Facebook, Instagram). In fact, Instagram and LinkedIn thrived because they had just a narrowly defined function. It fits how we have a double life. We keep work and private separate. We even separate apps.

But no such distinction exists in China. WeChat is used for everything, at home and at work. Life is adaptive.

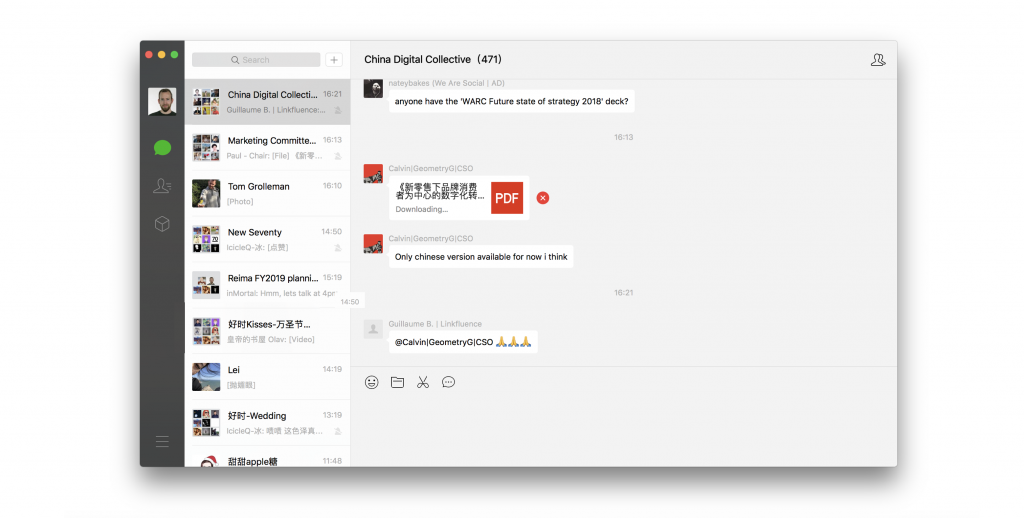

So below is my WeChat on my laptop. So you have a China Digital group with people I don’t know, same with Marketing Committee where a PDF is shared, my brother, Seventy Shanghai, two client project groups, my wife, another client group and a colleague.

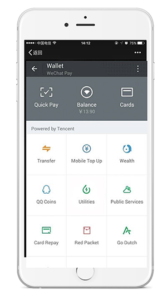

Rather than having narrowly defined function, WeChat is an operating system in itself, as it’s used for instant messaging, (video) calling, paying, shopping, meeting new people nearby, file transfer, a newsfeed, with 500 games and more than half a million mini programs. Imagine doing all that on Facebook. There would be an outcry on the collection of data. But in China, no such thing, because it’s not the individual that matters.

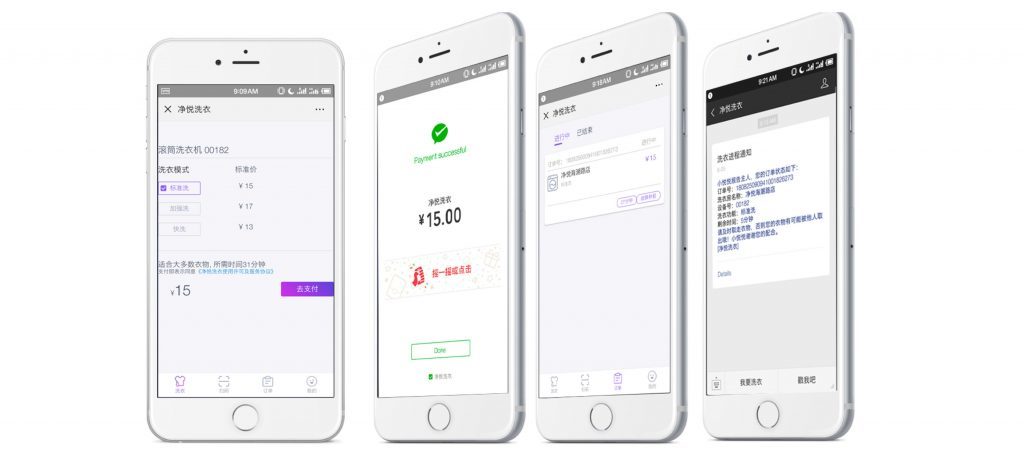

It feels like science fiction when you can scan a QR code on a laundry machine. So you scan this QR code, on one of the machines and each one is unique so it knows which one you’re using.

So you select the programme you want, and pay for it. It adds soap automatically. And on the app you can see how long it takes. And you get a notification when it’s done. Of course you send all your data to them as well. The staggering thing is not this itself, but the fact that you can easily combine on- and offline in ready-made templates, in existing software. This opens up a lot of possibilities.

QR codes on tables in a restaurants will open the menu within WeChat, from which you can select dishes, order and automatically pay. Because it’s a unique QR code, it already knows your table number.

So welcome! Select dishes, select quantity and order. Pay, voila!

In shopping malls you can scan karaoke booths, and the booths will know who you are when you enter, save your songs, or even broadcast them if you like.

There are sharing bicycles on every street corner. They open when you scan them and some also adjust their saddle to your height which is saved in the app. Still within WeChat.

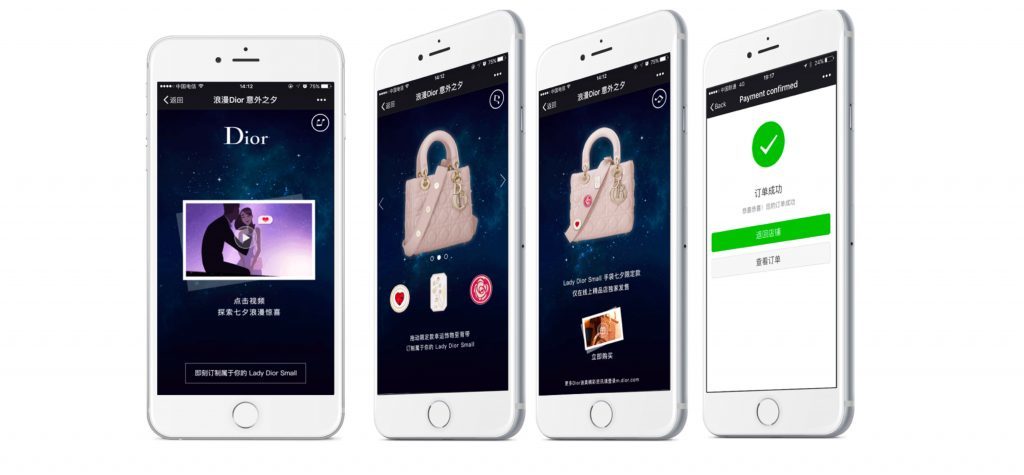

And you can follow brands and from their feeds instantly customise and order their products, like this example from Dior. So is this social media or e-commerce?

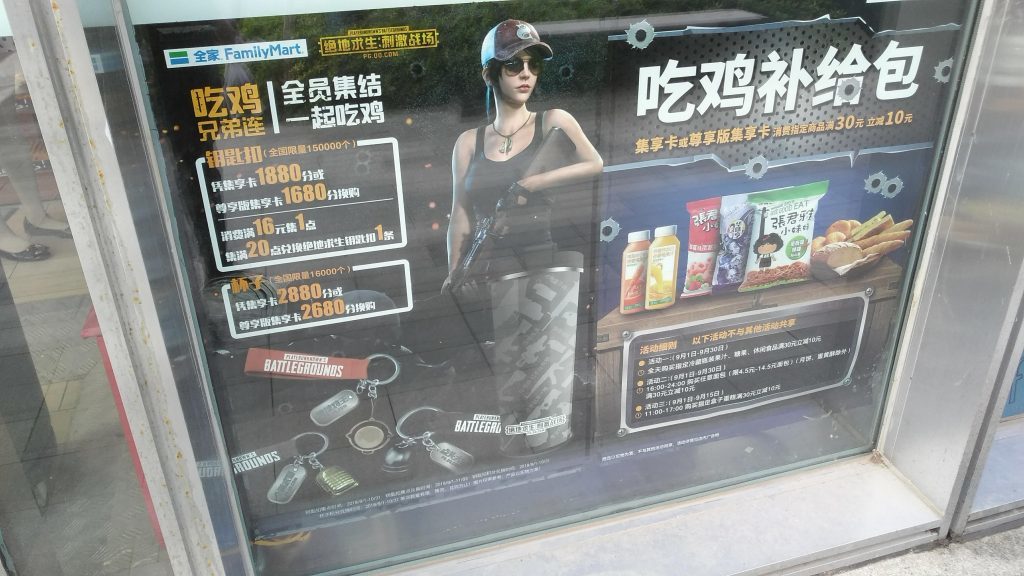

FamilyMart ran this promotion for the game PlayerUnknown’s Battlegrounds, where you scan the QR code of your coffee cup sleeve and play a WeChat mini-game to unlock keychains as well as in-game rewards (such as a FamilyMart shirt).

Powerbanks are available on loan in cafés, unlocked by a QR. The payment and deposit is handled automatically when you insert it back into the slot after use.

What about Alibaba’s HEMA supermarket? Which is a supermarket, food delivery and restaurant in one. It sounds complicated, but it’s simple.

So here I’m buying salad.

And some Dutch beer.

And when you’re done, you can simply pay through the app.

But you can also give them to the restaurant and they’ll cook them for you!

Or you can order it from home, and they’ll deliver it to you. There are people packing in the supermarket, and then they scan the items too, and put them in a bag that goes through the ceiling here, and goes to the delivery crew.

What about paying for fuel without ever leaving the car? Just get the mini-program of the fuel station.

Here’s a photo of street musicians in Xi’an, who don’t have an empty guitar case for money collection, but just show their QR codes instead. And the point is, this is super normal. Also beggars sleep outside with QR codes.

So when you shop online in the West, you do a lot of switching between websites. You search wedding gifts on Google but then some blogs recommend a tablet. You watch YouTube a video for the best tablets in the market, and watch another on the differences between Android and MacOS. You browse the Apple store, but on Pricerunner decide for a Samsung based on reviews. Then you view stores for prices and in the end, buy it from Amazon.

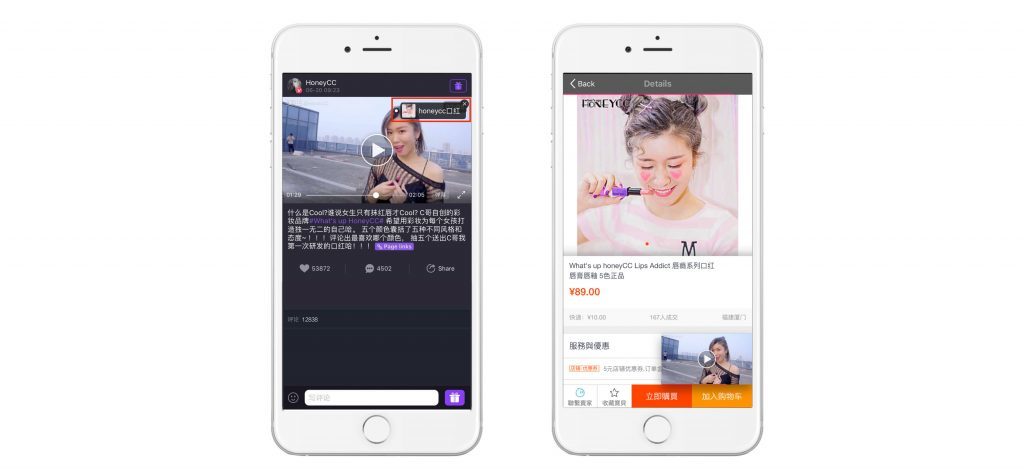

But dissecting China’s customer journey is much more messy, because everything is everything. Through the mixing functionalities, shopping experiences are often a mixture of discovery and purchase, brands and platforms make full use of the two being much more seamless than in the West. Take Meipai, a video streaming app, that integrates shopping. You see your influencer put on a lipstick you didn’t even know you were looking for, you ask her to put on a more darker shade of red, you decide you like it and buy it instantly while her live stream keeps playing. It’s delivered to your home in half a day.

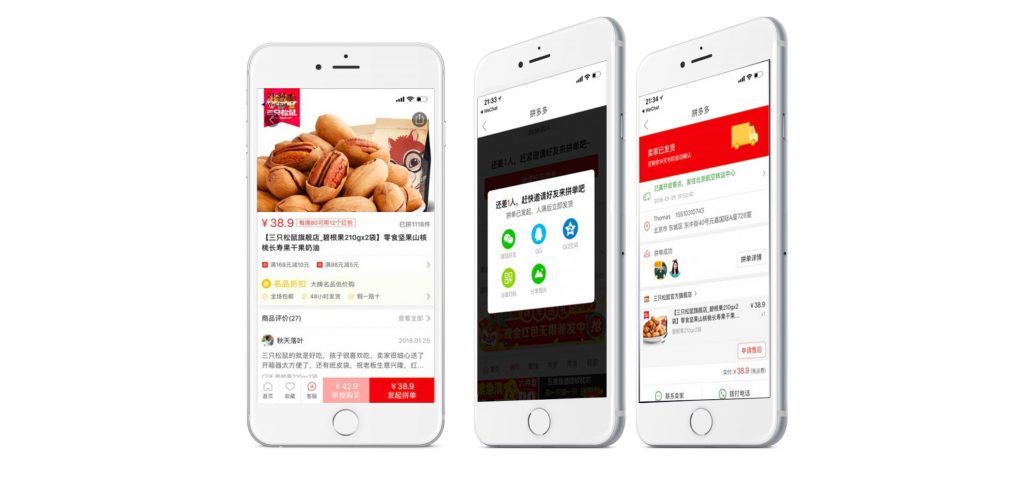

Pinduoduo, an app that lets people group up on WeChat, shop together and order items in bulk, directly from the manufacturer. Here’s the normal price, here’s the group price. The app is so successful because people share the bulk order on their feed, and invite friends through instant messaging.

AliPay is a huge payment app, but you can also play games on it. Save money, chat, order food and watch a movie. Even health insurance or train tickets. Does this all go back to the Chinese way of thinking, and refusal to categorize things? Is it context-free, let me see what I think about, and get me what I see. I’m not sure. It’s also a good business model to do everything and make a lot of money.

In China, I’ve had weeks where I just used WeChat and Alipay. But the last days traveling across Europe I used all these apps.

So why should we make sense of this?

Think about this: Chinese investors, government officials, and corporations have mapped everything in Europe and the United States. There are 600,000 Chinese students abroad. Not just USA, but also Europe. And these Chinese knows a lot more about us than we know about them. China knows a lot more about the West than the West knows about China. This is not a case of governmental protection. I think at the root, Western people are not really that interested in China.

And if we do think about China, we think in stereotypes. We think they’re oppressed, living under smog-filled skies, their factories making counterfeit iPhones. These stereotypes are just as true as Dutch people wearing wooden shoes.

But where to start when it comes to understanding China? It’s quite complex because due to its sheer size, and if we use the parallel of contextual thinking, everything is connected. A is true, as well as Not-A. For every social network in the West, there are 6 in China. Many of apps blurs online and offline, entertainment and purchase. But while WeChat does everything, the opposite is also true. Baby Tree, the biggest social networks for parents, has 200 monthly active users (same amount as like LinkedIn).

Everything is connected, and everything seems to be true. More Chinese are hitting the gym for the first time, and at the same time more Chinese are getting obese. Roseonly is a successful brand because you can only buy flowers for one person in your life, which builds on Chinese loyalty to family and your wife. But at the same time, twenty variants of condoms are for sale at every convenience store and there are private cinemas across the city, with a two-person sofa and a screen. What do you think people do in there? China is the world’s biggest importer of Rolls Royces, but the word luxury is banned for advertising, out of fear of protests on wealth inequality. You could say even the country is schizophrenic, being both communist and capitalist. It has tight control over its people and state firms, but also welcomes an open market.

It’s tempting to polarise China’s contradictions and extremes. Focus on how China is obsessed with frugality or indulgence. How respecting elders is key, or individualism. But not both. This is what journalists often do. Nobody wants to read about a sunny day when nothing happened. But by only looking at the black-and-white extremes, we forget the larger middle with shades of grey.

Modern China isn’t easily categorized and any attempt to do so would only be counter-productive. It’s about the relations in between that matter. This rings true for understanding both individuals as well as understanding media. Rob Campbell, in one of his presentations, said that you have to explore at least three sides of every topic to understand what goes on in the hearts and minds of Chinese consumers: the personal and private side, peers, and public and social sides.

When it comes to marketing, we shouldn’t focus on technological pillars or specific channels, but see how they relate to each other. Make it possible to easily switch from awareness to purchase (if we can even sort touch points on this distinction). Ask what can your phone do with your computer, what your car can do with your phone, what a WeChat mini-program can do for a newly bought t-shirt. Interesting possibilities arise. I think what the approach really comes down to making sure consumers can always see what they think about, and can always get what they see.