One of the hardest things to understand in marketing is the difference between differentiation (how different you are) and distinctiveness (how recognizable you are) — and which one is most important. It’s also where marketing’s biggest irony lies.

There are plenty of guru’s like Simon Sinek who say people don’t buy what you sell, but why you sell it. And they’re always full of post-rationalized lessons from the world’s most successful companies like Apple or Nike. There’s also this stuff about positioning grid and archetypes. It’s popular teaching in boardrooms and universities, because it’s just so simple.

The only caveat though is that there’s just zero evidence that any of this is true. Consumers just don’t think that deeply about brands and don’t perceive brand personalities or archetypes. Try it for yourself: open your fridge and see which product you bought because of its archetype. Which archetype is your milk? What’s the ‘why’ of your peanut butter?

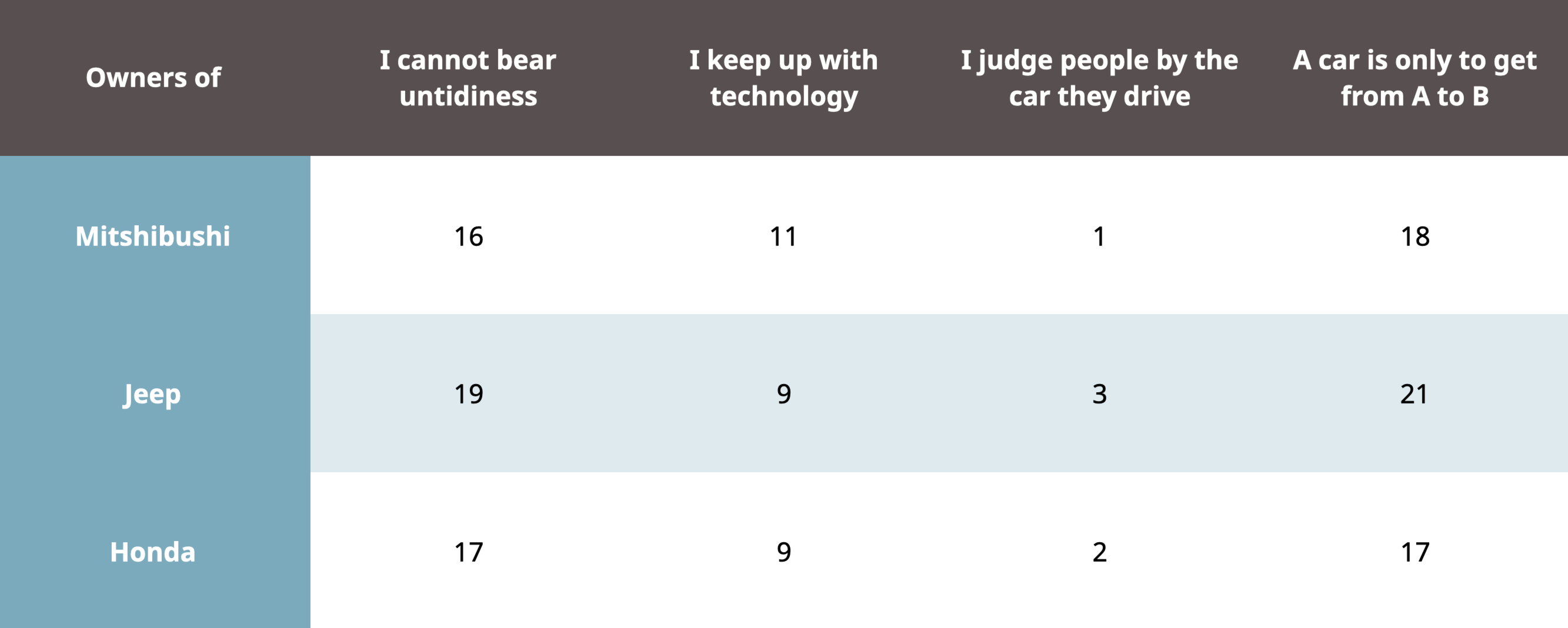

Here are some graphs from ‘How Brands Grow’, which shows that brands within the same category don’t sell to different consumers. Not just on emotional perceptions of what a car is, but also the demographics of its buyers. The differences are negligible.

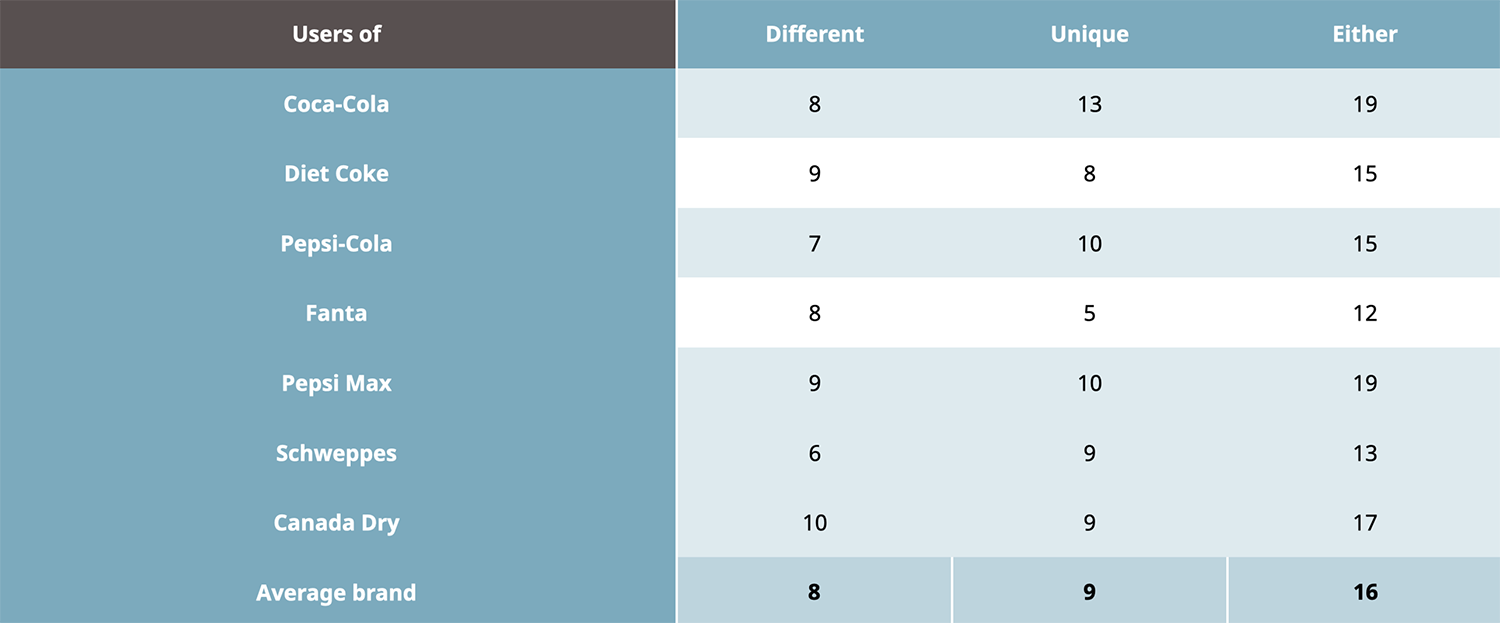

A salad brand may think to appeal to health-conscious consumers, while a chocolate brand appeals to those who look for indulgence. This sounds reasonable and managers may buy into that. But brands don’t necessarily sell to different consumers, not even across categories: I myself may have a salad for lunch and some chocolate with my coffee afterward. 72% of Coca Cola drinkers also buy Pepsi.

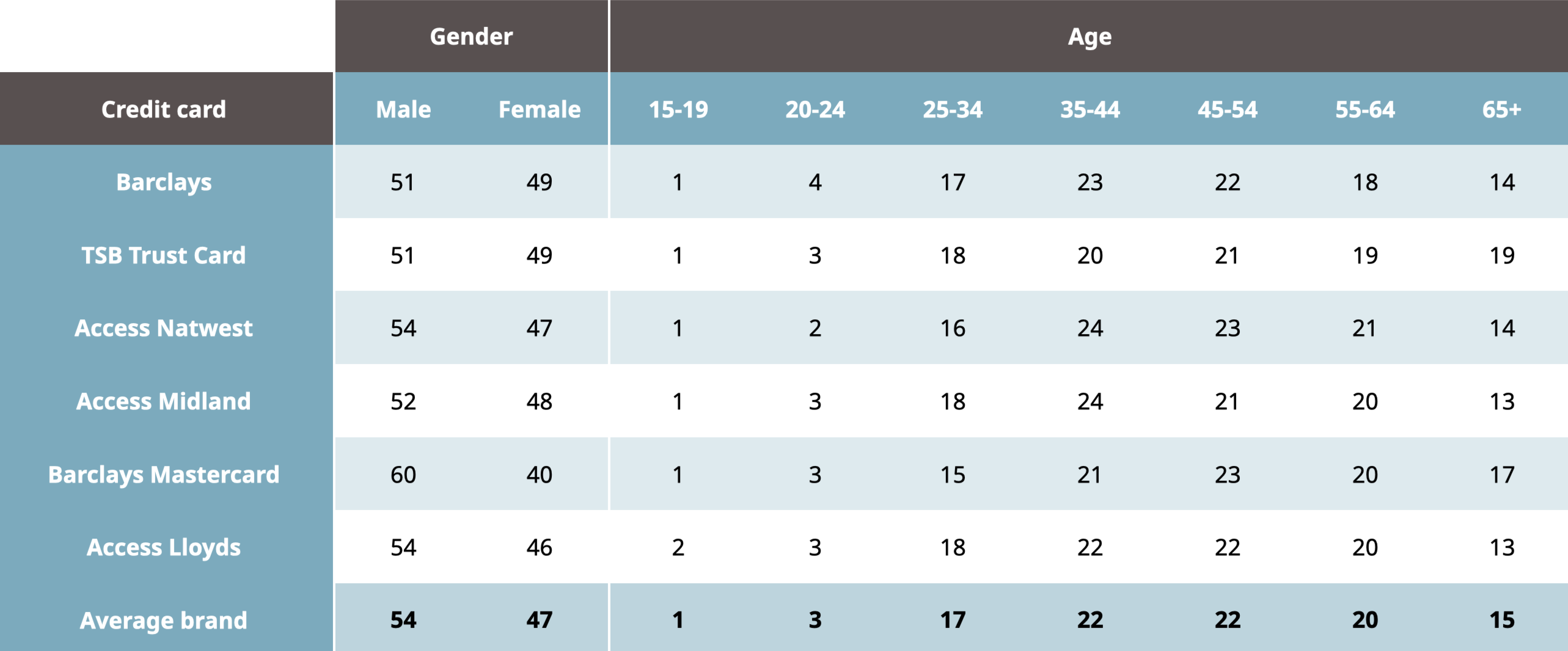

If people actually perceive brands as being intrinsically different, you think it would show in research, right? But again, there’s zero evidence that this is true. When asked, only 1 in 10 buyers perceives a brand to be different or unique.

In fact, brands are actually moving to be less differentiated. Here’s a McDonald’s in Suzhou that shows fried chicken, which is typically KFC’s domain, because Chinese fast-food consumers just like chicken a lot and it provides more marketshare than beef burgers. Also Pizza Hut is advertising its chicken-topped pizza’s.

Further proof lies in the slogans of three of the world’s biggest brands. Apple’s ’Think different’, Nike’s ‘Just Do It’ and McDonald’s ‘I’m loving it’. I’m really struggling to find anything more generic than those sentences. They don’t say anything unique at all. They’re not intrinsically different. Instead, these brands are extremely distinctive. And this — instead of by being different — is how brands are really built. It’s why McDonald’s is selling chicken, just like KFC, but as a brand it’s very distinctive (the golden M versus KFC’s Colonel.)

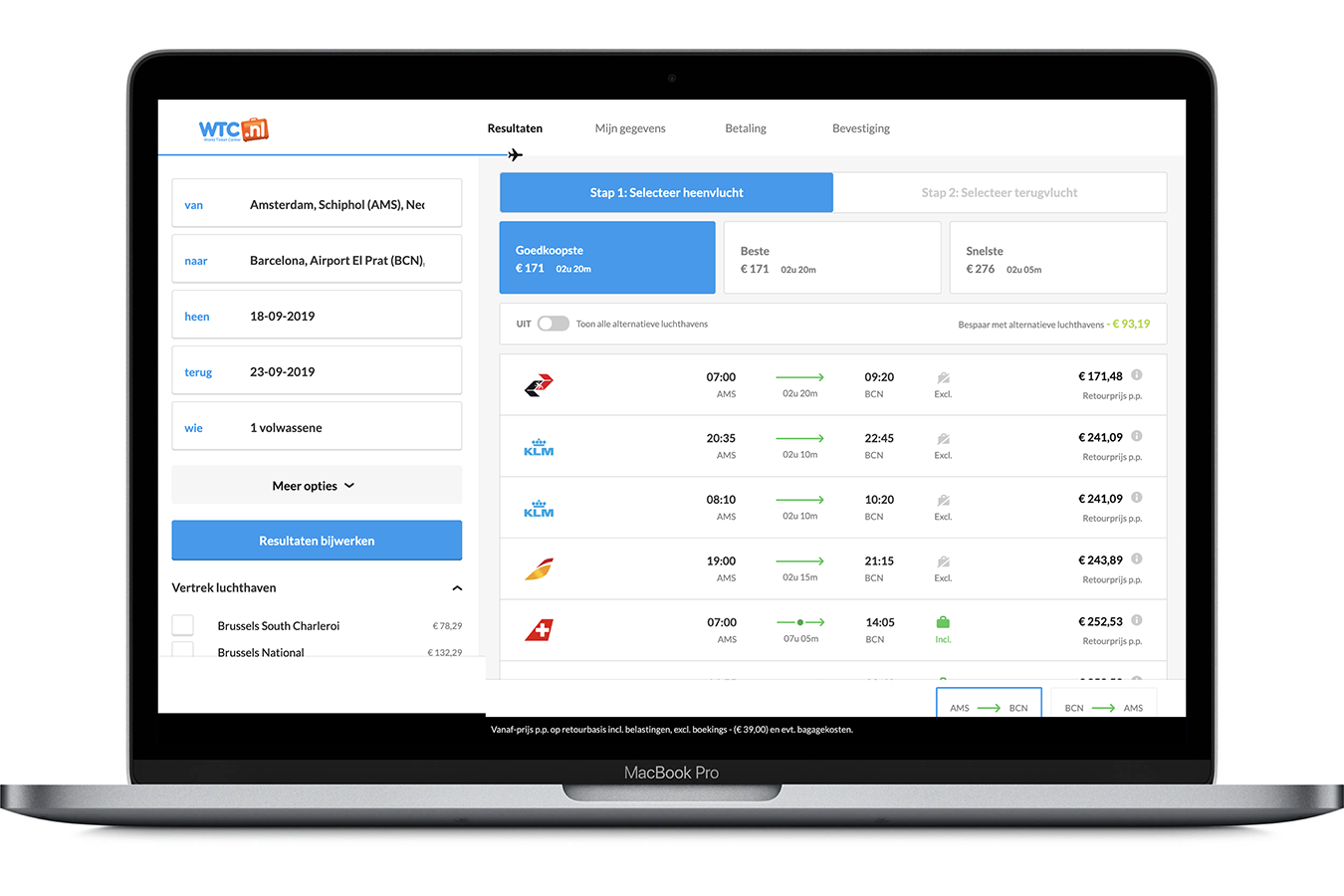

Distinctiveness is so important because people don’t really care that much about brands. Shoppers don’t study brands, they don’t engage with brands, and they don’t want brand experiences. They just buy. People only spend around 13 seconds to decide on a product in-store. Maybe it’s longer — let’s say 3 minutes — for buying online airplane tickets, but not long either. Brands help us make decisions: how would we ever choose between thousand of shoes without brands?

When we buy products, whether it’s ketchup or online plane tickets, we simply pick the ones we know because it feels good. And even if there’s another brand cheaper, like on this price comparison website for plane tickets, I’ll probably opt for KLM since it’s not that much more expensive.

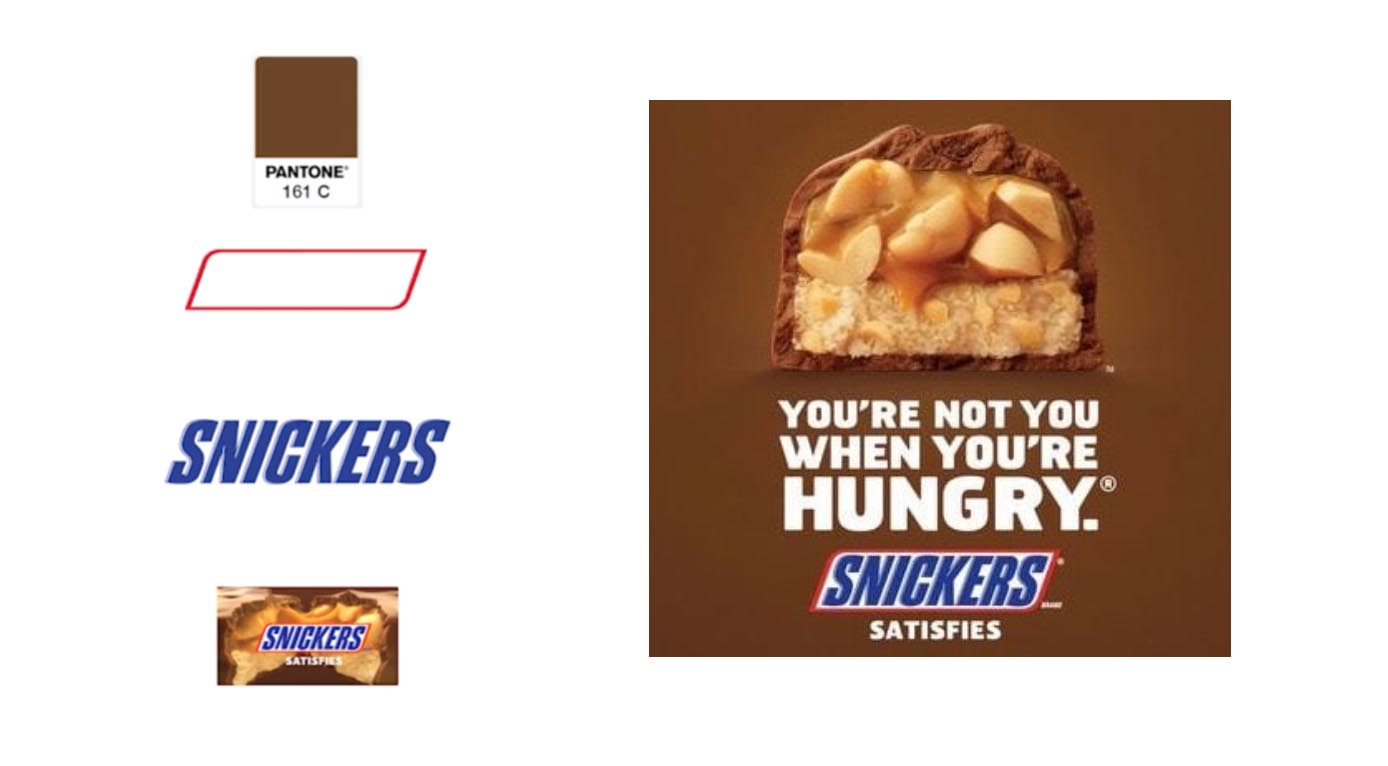

So brands try very hard to be very familiar: distinctive. You can probably quickly guess which brand this is, only from glancing at the color from the corner of your eye.

Starbucks has distinctive brand assets such as the green color, the logo without words on it, the white cup, the green aprons, and even names like Frappucino and Venti are distinctive to Starbucks.

Here are Snicker’s brand’s assets dissected:

Look at this shelve from a supermarket. Your eye will try to sort it into things you know, and your eyes (and hand) will be drawn to brands you know. When you stand out, your product is easier to be chosen.

This pattern-making applies to everything, also applies to places. Paris has the Eiffel tower, and so much more. If you’re deciding between going to Paris or Milan, you may go to Paris earlier because it feels more familiar. What can you do in Milan?

So here’s the irony:

If people don’t need brands to be differentiated in order to buy them — if the vast majority of people don’t even perceive brands to be different — if brands simply need to be distinctive — then what’s the role of creativity and branding and marketing?

Maybe further questioning this answers itself:

Can we just make a logo for 30 seconds and put that on TV? Can we just spam our logo everywhere like Vivo and Oppo are doing? The answer to that is: yeah, probably. But it’ll be very expensive.

Back to the first point: Brands don’t need to be different to be bought — but this doesn’t mean that creativity isn’t important. It just means the role of being different is not the same as commonly understood. The irony is that even though consumers aren’t good at remembering differentiation — nor that they care, it does helps a brand to stand out and therefor build distinctiveness. Distinctiveness is the goal, differentiation (one of) the means.

But as a term it’s misleading. It’s not about those brand archetypes or positioning grids. Yes, being different helps, but it can be just as simple as being yellow while all other brands are blue. Phrased in another way: Being interesting and standing out is far more important than actually being different.

Here’s why:

The goal for brands is to become famous, memorable, and distinctive. That every consumer knows them, and that they’re mentally easily recalled when shopping in-store or online. That they feel familiar, that they feel good because we know them. That they’re easy to be remembered and easy to be recalled and therefore easy to buy.

Now let’s look at the following ads. If we’re advertising to make our brand memorizable, then these ten watch ads are clearly wasting money? Remove the logo and I have no idea which brand is promoted. (In fact, I think the first one is an ad for Nespresso, because Clooney is so extremely distinctive for the coffee brand.)

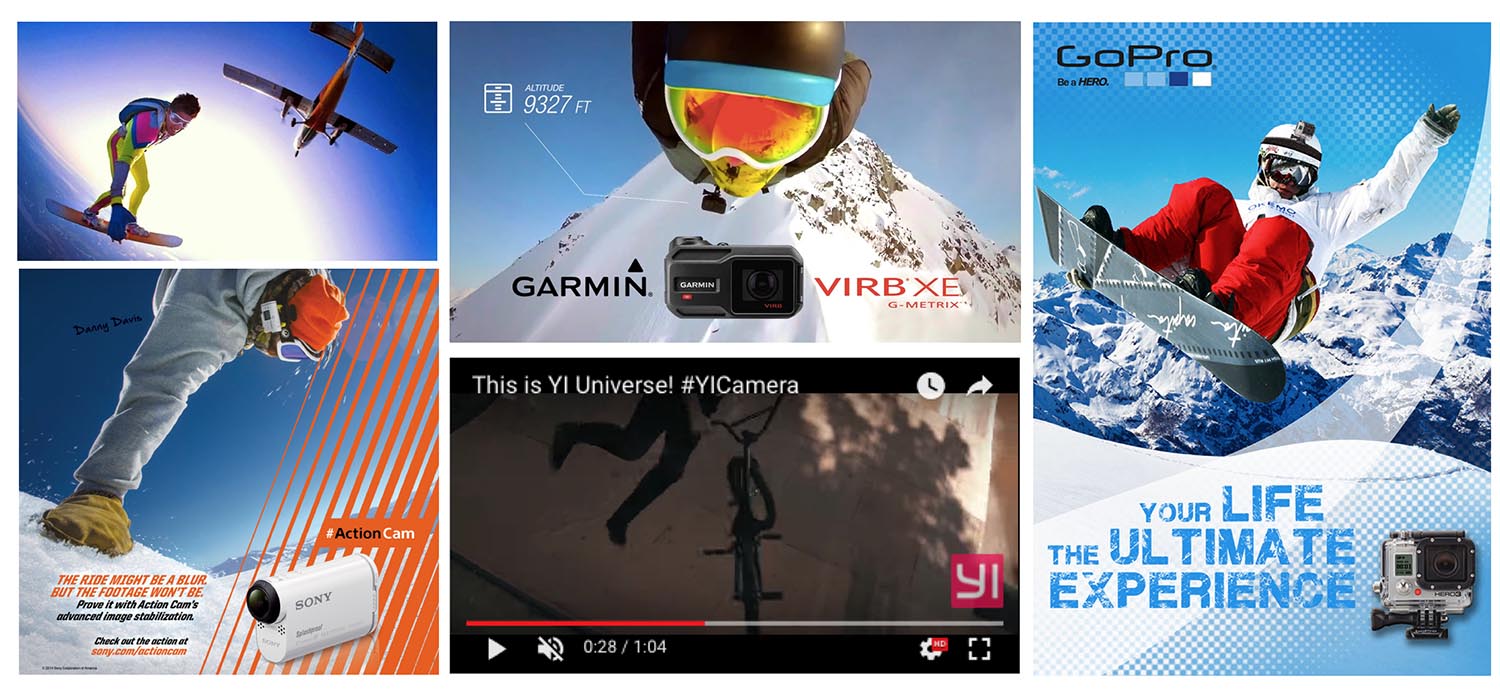

It’s the same for these action camera’s:

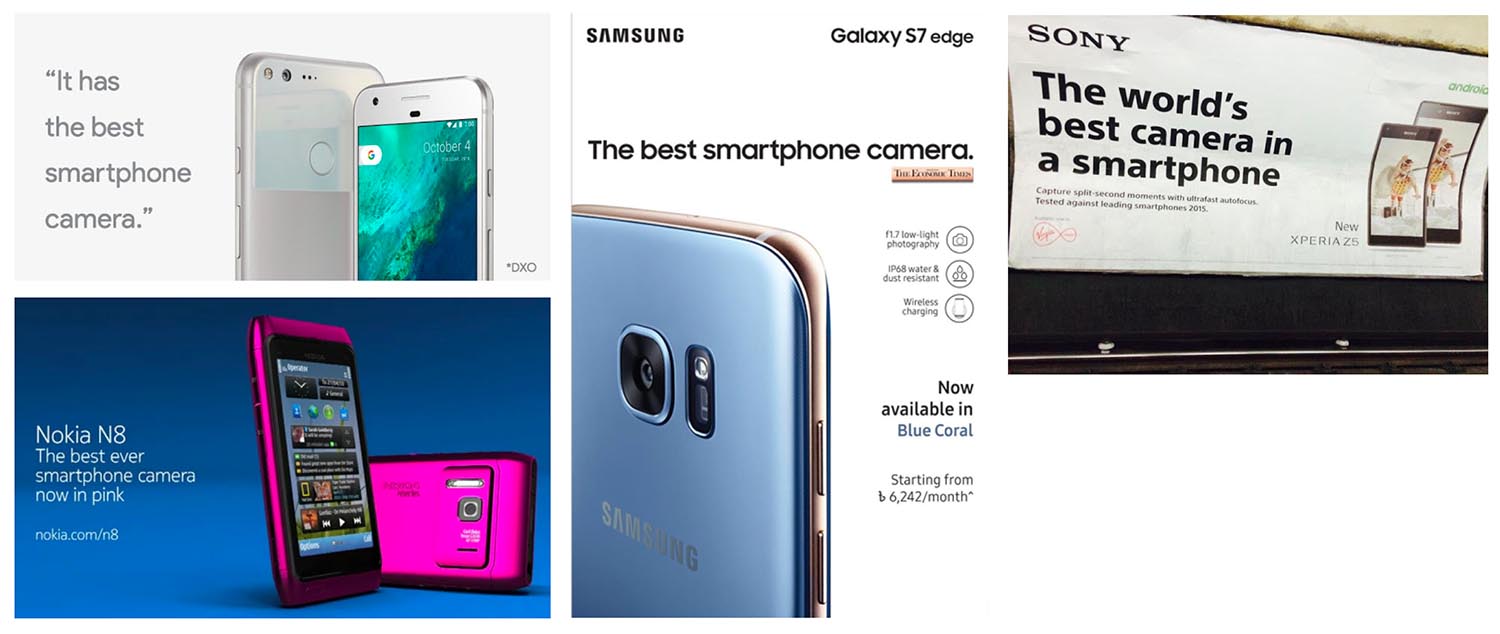

Or these smartphone advertisements, who even use identical text:

These ads are not distinctive, differentiated, nor interesting. They’re so boring, I wouldn’t even properly look in the first place. And this is also backed up with data. Most advertising doesn’t even get the basics right as just 16% of advertisements get remembered and correctly attributed. I wouldn’t be able to correctly recall those advertisements above.

Compare this Swatch advertisement to the watch ads above. There’s no clear ‘why’ and the positioning isn’t visible (whereas the other watches are more clearly ‘Successful businessman’). But Swatch stands out. Not only is the ad differentiated (colorful compared to all that blackness), but most of all, it’s interesting. Compared to the other ads, it makes you look.

Being interesting is more important than being different. But the irony is that being different can be interesting.

Being interesting is what gets you noticed, remembered. People don’t need to think very deeply about your brand* (because they won’t).

I would describe the ironic crux as following:

At the core, brands don’t need to be inherently different to other brands. It can provide exactly the same services or product (it’s very likely it does, and it’s not as different as you think it is). But your brand must be distinctive. Consumers need directly recognize your brand, they cannot confuse it with another brand. Your brand must feel familiar, it must be easy to be recalled and easy to be chosen as a safe choice. It must be an intuitive choice. For this, it needs to be distinctive, otherwise, they cannot recognize it. This can be as shallow as having a yellow identity, while the competition is all red or blue. Being different isn’t as important as being interesting, because being interesting helps you to be noticed and be remembered — but being different is just one form of being interesting. It’s just not the ultimate goal. Being distinctive is.

Sources:

- How Brands Grow, Byron Sharp

- Distinctiveness doesn’t need to come at the cost of differentiation, Mark Ritson

- Mark Ritson and Byron Sharp should hug it out on distinctiveness vs differentiation, Shann Biglione

- Why Being Interesting Might Be More Important Than Being Different, Martin Wiegel

- 10 numbers every marketeer should know, BBH Labs

- Eat your greens, APG Ltd

- Make the most of your brand’s 20 second window, Nielsen

- Most advertising doesn’t even get the basics right, Lucian Trestler

*Disclaimer:

Yes, you may think: “But there are some people who deeply care about my brand!” And you think your brand is different. But it’s not. And even if it is, thinking so is dangerous. If you are a brand manager, you’re like the proud parent at the playground, who thinks their child is the smartest, most handsome – and very special. But other parents know that that isn’t necessarily true (about your child), because they think the same about their child. If you’re a brand manager, your view is as biased as it can get. Yes, some people care deeply about your brand and read its very blogpost. But the majority of people don’t. And your brand isn’t different. To think so is damaging your opportunities. You’re not a niche brand that is the exception to the rule. The consequence is that it’s dangerous to rely too much on a brand story, on a brand personality — to rely mainly on social media. Two-thirds of people don’t follow a single brand on social media. So you keep reaching the same people, over and over. Brands only grow through the acquisition of new customers. Not just that. The vast majority of customers are only light buyers. This is true for brands like Coca-Cola as well as small brands. Another last point is that the people who read your every blogpost will buy from you anyway. You’re wasting your time and energy with them.