The first time I drove Suzuka, virtually, was probably on EA Games’ F1 2000, manoeuvring a pixelated car around with the left and right buttons of the PS1 controller. Through the next decade, I raced the Japanese track in games like Grand Prix 4, Codemasters’ F1 series, and Gran Turismo 5, so I felt I knew the track quite well. Heck, I even felt I was pretty good at racing.

But a new generation, including rFactor, Assetto Corsa and iRacing, deceitfully look like games, while their single purpose is to simulate exactly what it is like racing cars.

Onboard the MP4-30.

These sims are brutal. They leave no pleasantries for what could be called ‘casual gameplay’; they only have the cockpit camera, there are no assists, and tweaking the setup of the car is overly-complicated with dozens of parameters. The driving itself is finicky, making it difficult to constantly replicate good laptimes.

Though, to help you cope with this, the sim aids you by constantly communicating. The tracks are laser scanned and yield every bump in minute detail. The suspension is constantly reacting to it, and through the force feedback of the steering wheel you can feel the car sliding and adjusting. You can hear the tyres searching for grip and the engine for revs. You’re using all of your senses to go faster, and any moment with a lack of focus is immediately penalised. There isn’t the physical aspect that real racing offers, but mentally, sim racing is draining.

This all makes it a lot like real life, which is the whole point. Lots of racing drivers, like Max Verstappen, use simulators at home. It’s quite telling that the move Verstappen pulled off on Felipe Nasr at Spa, was practised in iRacing first. Nobody would try to go around the outside through Blanchimont, but come the real race, he knew he could do it.

Driving around Suzuka in iRacing is unlike any other racing game.

When I tried a Formula 1 car in iRacing — after all these fast laps in all those other games — the illusion of myself being a proper racing driver was immediately shattered; I span the rear wheels, locked up the fronts and crashed halfway through the first lap. I was terrible. And for at least a quarter of an hour, I struggled to even get a clean lap in. Every time I was surprised by the corners. Everything seemed totally new, even though this was the Suzuka I’d grown up knowing.

Driving clean is a minor step, but going faster is the big one. For that there are plenty of tutorials on driving, and explanations on the physics of the cars and the tyres. Across all simulators drivers have formed teams to share lessons and setups and to compete in leagues. Some teams, like Coanda Simsport, have official sponsors, and their races are broadcast online. I was invited for a session with Coanda’s top driver, Martin Krönke, by Virtual Racing School (VRS), who have built telemetry software especially for iRacing.

Martin is from Germany, and is one of the fastest sim racers in the world, having won several races in the World Championship Grand Prix Series – the virtual F1 equivalent. He also coaches drivers via VRS.

I rightfully expected to be completely trashed, but to prepare myself as best as I could I spent time with the McLaren MP4-30 on Suzuka for some hours. We then compared my best lap time to Martin’s (except Martin needed no practice). I was happy my 1.37.0, as I got all the lines right and I didn’t lock any wheel. Yet, Martin went over four seconds faster, at 1.32.9, gaining chunks of time in every single corner.

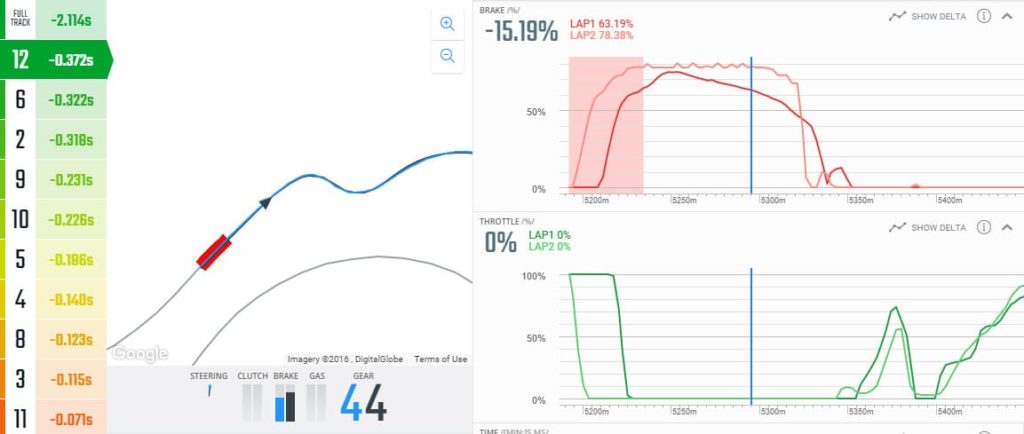

From the replay our driving styles looks similar, but the differences are clear when looking at the telemetry. Below here, you can see an overview of the software, which provides all data like driving line, speed, gearing, steering angle, G-force, amount of appliance of braking, throttle, rear wheel spin and front wheel slip.

An overview of VRS, were you can see things like your line, speed, gearings, steering angle, G-force, brake %, throttle %, rear wheel spin and front wheel slip.

In more detail, below here, is the data for the Casio Triangle section of the circuit. This was where I lost the most amount of time overall in comparison. Martin’s braking (dark red line) is shorter and much, much smoother. He also manages to start steering while still applying a bit of braking, crucially without locking a wheel.

Even though Martin’s initial cornering speed is lower, his racing line (blue) is tighter, and he has a better exit out of the corner. I braked hard, applying the throttle (light green) mid corner, while Martin just carries more speed into the second kink. He then applies the throttle (dark green) earlier, carrying all that extra speed out onto the straight.

Then below here is the data for the notorious Spoon Cure, where I lost 0.747 seconds alone. Martin (blue), turns in later, again giving a better exit in return. Though again my speed in the middle of the corner was slightly higher, I still had more braking left to do (light red). Martin touched the apex of the corner earlier and carried more speed through the corner. We accelerate at the same time, but at that moment Martin is already travelling some 15 KM/H faster than me, a difference that benefits him all the way to 130R.

As we analyse all the corners of the track and I’m baffled. I couldn’t imagine going into this much detail in any other game, but iRacing’s driving has the depth for it. The telemetry shows everything, and I make notes and try to memorise it all as I go back on track, to put the lessons into good use.

Applying Martin’s lessons immediately makes me faster. I’m memorising braking points, where to steer and at which part of the curb to hit to optimise the apex. As Martin taught me, there are plenty of corners where hitting the outside curb isn’t worth it, because it compromises the next corner. The Esses are a fine example of this. After half an hour, I compare my new best lap — now 1.5 seconds faster — to Martin’s initial lap.

Suzuka Esses, Martin Krönke on the left, myself on the right.

From the telemetry I again learn new areas to improve, which eventually, I do. While I still severely lack Martin’s finesse of driving – I cannot brake as late as him — I bring the McLaren around in 1.35.0, a time that at first seemed completely impossible for me.

Looking at the telemetry again, I can see my improvements. In the screen below is Casio Triangle, where now instead of a near-full second, I’m losing ‘only’ 0,372 seconds to Martin, and our lines are much more similar.

Applying lessons learned.

Still, the lap isn’t perfect (I slightly locked the fronts going into Spoon, and I missed the apex of the first Esses). Martin and me are 2.1 seconds apart, which would put any F1 driver to shame . (Martin’s time would have been good for third on the grid for last season’s Japanese Grand Prix, while my lap would still be 0.6 seconds faster than Button’s qualifying effort, albeit in different track and weather conditions.)

But iRacing, coupled with VRS is incredible. This is not a game you play, it’s something you study. After three hours, I’m mentally exhausted, but desperate to get back into the cockpit tomorrow. I’m confident I can improve the time even further, thanks to depth of the game, it’s honest feedback and the telemetry.

But, I’m happy still — for now — as at least the illusion of me knowing how to drive Suzuka is slightly restored.