“One day, a Dutch driver should claim success in Formula One, and I want to be that one”, said a boy full of dreams. And just when the boy, then a grown man, looked to fulfil that promise, rivalling those who went on to do just that, all that promise and all that future was taken away in the blink of the eye.

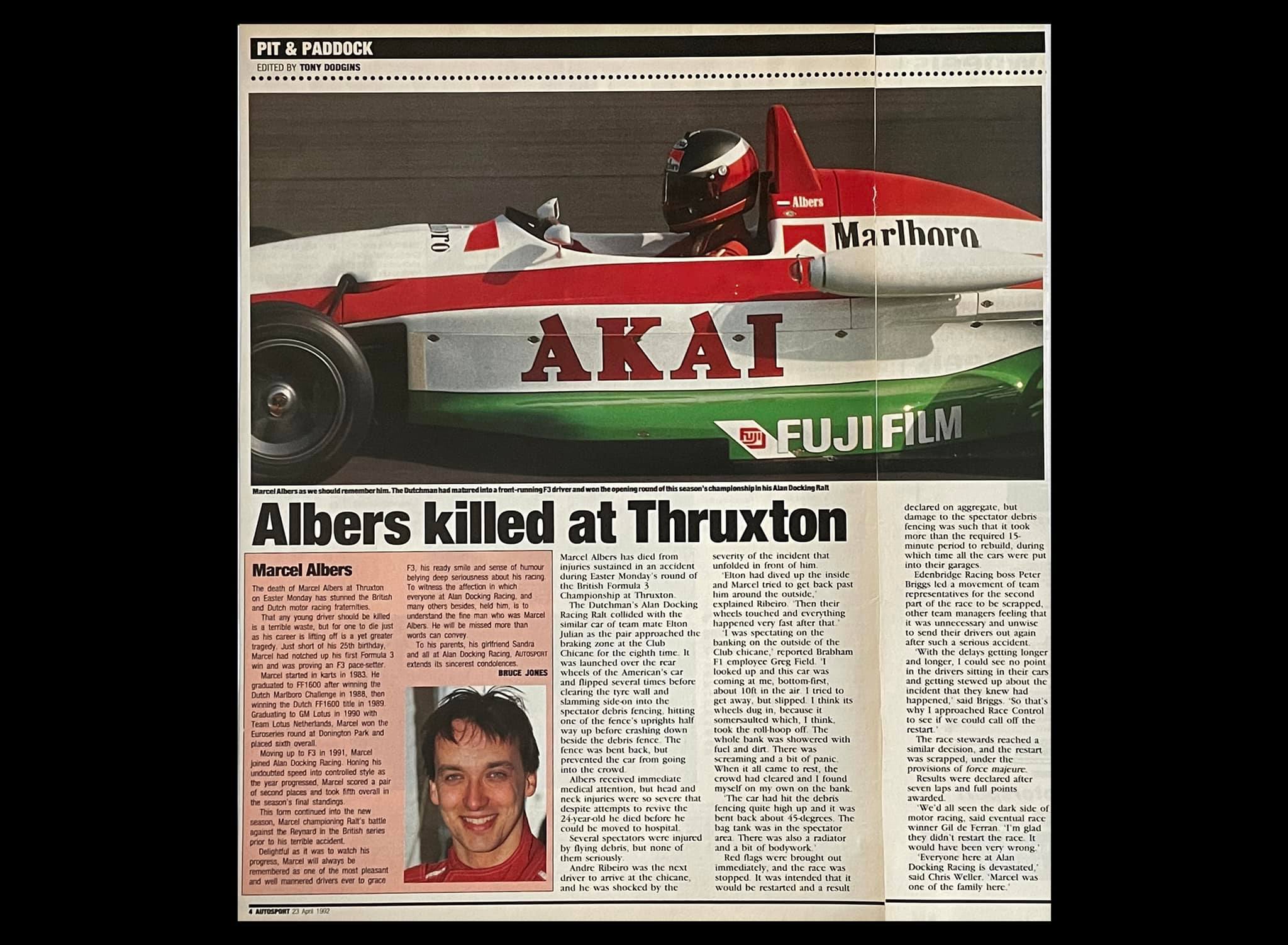

On a Thursday in April of 1967, Marcel Albers was born into a family with his mother Jeannette, his father Jacques, and his brother Ronald. The family was well-off, as father Jacques owned an electronics store and importer brands like Akai and Fuji. Marcel grew up in the Dutch city of Rotterdam, and Ronald — three years Marcel’s senior – was better at everything, the way older brothers are. Ronald became a three-time hockey champion and later received a kart for his birthday.

Ronald raced at a karting circuit in the nearby village of Strijen, where he went with Marcel and their father, the kart sticking out of the boot of the family sedan. Marcel initially watched but would later try the kart as well. “Marcel was around eleven years old when he started to drive Ronald’s kart regularly, even on the street. On Marcel’s eleventh birthday, one of the brothers damaged a brand new car of which was parked in the street”, Jacques would recall, as he can’t remember which brother caused the damage. Marcel was hooking on racing, and also raced a petrol powered radio controlled car. When Ronald lost interest in karting, Marcel continued.

Marcel drove his first kart race at the age of sixteen, and although he proved apt behind the wheel, karting remained a hobby. His father allowed karting but disproved of motorsport.

Marcel’s first car was a diesel-powered Volkswagen Golf, which he used for his daily commute to school. Jacques: “Marcel had this one teacher who couldn’t drive. When the teacher arrived to park, he’d step out to see how much space there was. Sometimes he’d leave the vehicle twice to look. When Marcel arrived, he made a hundred-and-eighty-degree turn and in one move parked his car next to his teacher’s. I got a phone call from the school principle who thought it was dangerous, and I said it wouldn’t happen again. But Marcel could do it ten times over, precise to the centimetre.”

Marcel went on to study economics in the Belgian city of Antwerpen but never let go of karting, or cars for that matter, as his Golf was fitted with a turbo. When Marcel asked his father again whether he was allowed to compete in motorsport, the answer was still no. “Then I’ll do it on my way”, said Marcel, and promptly he signed up for the Marlboro Challenge, a talent hunt by the Dutch Racing School at Zandvoort. Jacques didn’t worry: “What were the chances that Marcel would be the best out of 15,000 competitors?” That what was, until Jacques received a phonecall from Marlboro who asked for Jacques’ consent. Marcel was among the last hundred candidates.

Albers in his pitbox– Copyright © Stella-Maria Thomas

Marcel won the categories of both single seaters and touring cars, and eventually the Marlboro Challange. The prize was a season in Dutch Formula Ford 1600 with the Van Amersfoort team. That year, Albers debuted with a second place and won his second race. Three more victories meant he clinched the title with one race to space, in his rookie season. Marcel stopped his studies, and Jacques approved. He was now fully behind Marcel’s ambition.

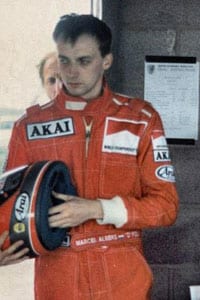

Marcel had grown to a tall young lad who was funny and witty once you got to know him. A guy who you could live next door to. That was until he put his helmet on. Once behind the wheel, Marcel seemed so in tune with the world, as tough and relentless and quick as anyone, oozed with complete happiness of sitting where he was sitting.

Several team managers across Europe took note of the stellar performance of Albers, and in the winter of 1990, Albers tested for two British Formula 3 teams; those of Eddie Jordan and Alan Docking. Especially Docking felt that Albers needed more experience than his single season in Dutch FF1600, and Albers took the advice. In 1990, he raced a full season in the German Formula Opel Lotus series, en route to sixth place, only five points behind David Coulthard. Rubens Barrichello won the title.

Marcel with journalist Hans van Onsem at Donington, 1991 – Copyright © Stella-Maria Thomas

Alan Docking had seen enough and signed Albers for the 1991 season. British F3 was one of the most prestigious and competitive stepping stone classes to Formula 1, and the 1991 grid was one of the strongest in its history, with Rubens Barrichello, David Coulthard, Gil de Ferran, Pedro Diniz, Rickard Rydell and Jordi Gené all present.

Albers arrived in fashion, and in his first ‘slicks and wings’ car race, he finished a neat third place. Five more podium finishes followed that season, as he finished fifth in the seasons standing. Barrichello was crowned champion after a close battle with Coulthard.

Marcel Albers battling with Belgian driver Mikke Van Hool – Copyright © Stella-Maria Thomas

In 1992, Barrichello, Coulthard and Gené moved on to Formula 3000, so it looked as if the season would become a duel between De Ferran and Albers. De Ferran drove for Paul Stewart Racing, who competed with a Reynard chassis, which seemed to have the edge on the Ralt’s chassis that Alan Docking Racing used. Over the winter, Albers tested tirelessly with Ralt’s designer Andrew Thorby to improve the design’s speed, the team impressed with Albers’ willingness to learn and improve the car to its finest detail.

Albers in the improved Ralt RT36 – Copyright © Stella-Maria Thomas

At Donington, the opening round of the 1992 season, Albers justified his role as a championship favourite as he took pole and went on to take the victory. Jacques was there to celebrate with Marcel’s first win, as Thorby was moved to tears by their work paying off. Then came the second race, at Silverstone, and after setting the fastest lap and challenging for the lead, a mechanical failure struck Albers’ Ralt. De Ferran won, as Albers retired.

The third race of the 1992 season was held at Thruxton two weeks later. With a new engine in the back of his Ralt, Albers qualified in second place, with De Ferran clinching pole position. At the start, Albers shot into the lead of the race, masterfully controlling the Ralt. The Dutchman used each inch of the track with De Ferran on his tail. This was racing at its finest; two youngsters at alienate levels of concentration, determined to prove themselves to be good for Europe’s Grand Prix racing elite. A classic race to the finish seemingly lay in prospect, but instead, the darkest of days was to come.

Marcel’s Ralt suffered gearbox problems, and he fell back to sixth place. He regained some of his early pace and came across his teammate Elton Julian. Just before the braking zone of the Club chicane, Albers tried to overtake Julian, but instead, the two cars collided. Albers’ Ralt was launched into the air and after what seemed like time slowing down, his car smashed into the safety fence, upside down.

The impact broke the roll bar of the car. Albers was removed from his car but died on the way to the medical centre. He was just five days shy of his twenty-fifth birthday.

Albers was buried in the Belgian village of ‘s-Gravenwezel, near Antwerpen, the city where he studied.

Copyright © Richard G. Hilsden

All of the promise that Albers had shown was swept away in that instant. Albers’ former rivals went on to greatness; Barrichello and Coulthard together winning twenty-four Grand Prix in Formula 1, and De Ferran becoming the 2000 and 2001 Champ Car champion, and the 2003 Indy 500 winner. Instead, Marcel’s run toward greatness stops in 1992.

Yet, there is something. Inside the paddock of Zandvoort, quietly hidden away, is a sign that read ‘Marcel Albers Street’. It’s the place where Marcel started his career, and where many other Dutch young drivers would follow, including a Dutch youngster who won his first Grand Prix this year. Like Albers, Max Verstappen also drove for the Van Amersfoort outfit.

Alan Docking looks back at his pupil with much sadness and love: “It’s cruel how one of the nicest guys in autosport was torn away from us. Everybody loved Marcel, the mechanics, the girls, me.”

Frits van Amersfoort: “You could laugh a lot with him, but he was also serious and motivated. The kind of driver you want for your team. It’s a disaster when drivers put all their mistakes at the team, Marcel never did that.”

Alan Docking concludes: “Marcel had a special heart. If it was only about the Sennas and the Mansells in racing, I’d immediately quit. It’s because of the guys like Marcel why I love motorsport.”

Alan Docking with Marcel Albers in the Ralt RT35 – Copyright © Stella-Maria Thomas